Active Surveillance in Small Renal Masses

In this interview we discuss a new study that looked at the outcomes of patients with small renal masses who were followed with active surveillance.

As part of our coverage of the 2017 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Genitourinary Cancers Symposium held February 16–18 in Orlando, Florida, we are speaking with Phillip M. Pierorazio, MD, an assistant professor of urology and oncology in the Brady Urological Institute at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and Ridwan Alam, a medical student at Johns Hopkins who conducts research in Dr. Pierorazio’s lab. Mr. Alam presented prospective

Cancer Network: First, Dr. Pierorazio, could you tell us how small renal masses are typically diagnosed and what the standard course of treatment and/or monitoring is for these patients? What is the typical prognosis?

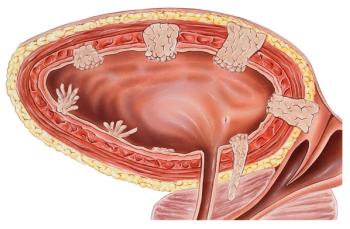

Pierorazio: Most small renal masses are diagnosed incidentally. They are actually the most common renal mass that we encounter in the United States now-about 60% to 70% of kidney tumors. As incidental findings, most of these tumors are actually not dangerous. We find that 30% of small renal masses 4 cm or smaller are benign, and the vast majority of the cancers are low-grade, indolent, or basically benign behaving cancers. This leaves only a minority of patients with potentially aggressive or dangerous tumors. That being said, this poses a real quandary because we know most of these tumors are not dangerous, but for the few patients who have dangerous tumors, how do we actively identify them and how do we minimize their risk of cancer?

Cancer Network: Ridwan, you analyzed patients diagnosed with small renal masses who were followed with active surveillance. Can you tell us about the design of the study?

Alam: Dr. Pierorazio created the DISSRM registry in 2009-DISSRM standing for delayed intervention and surveillance for small renal masses-to determine if active surveillance would be a safe option for patients with these tumors. He wanted to compare this [active surveillance] group with patients who underwent primary intervention like surgery. In this prospective study, patients with small renal masses from Johns Hopkins, Columbia University, and Beth Israel Deaconess were sorted after counseling based on the type of management that they decided to pursue, either primary intervention or active surveillance. We followed these patients over time, since time of enrollment, to see just how they fare with respect to survival and other clinical parameters we were interested in. Of course, there were patients who initially started off with active surveillance and then had intervention at a later date, the delayed intervention group. For our analysis, we used an intention-to-treat model, which means that anyone who crossed over to delayed intervention was grouped in with the active surveillance group because that was their original exposure.

Cancer Network: What did you find in your analysis?

Alam: The outcomes we were most interested in were cancer-specific survival and overall survival, and what we found is that at 7 years cancer-specific survival was similar between the active surveillance and primary intervention groups, with the rate of survival near 100% for both groups. However, when we looked at overall survival, we found that patients in active surveillance had lower rates of survival at the 7-year mark when compared with patients in the intervention group. This discrepancy between the cancer-specific and overall survival rates actually tells us that active surveillance patients are dying from other causes, causes other than kidney cancer. This makes sense because these patients are older, have more medical comorbidities, and lower performance scores than the primary intervention patients. This is actually really encouraging data because it tells us that the surgeons are doing an excellent job of choosing patients that are appropriate for, and more importantly, who will be successful in active surveillance. Our ultimate conclusion is that active surveillance is indeed as safe as primary intervention for patients with small renal masses at the 7-year mark.

Cancer Network: Dr. Pierorazio, was there anything particularly unexpected and interesting about these results?

Pierorazio: One of the more interesting points from Ridwan’s analysis of these data was that there were two deaths from kidney cancer and both of these patients has undergone surgery. When we first analyzed these data a few years ago, our follow-up was, as expected, a little bit shorter and we really didn’t see any differences in overall survival. What we are seeing now with a median follow-up of about 3 years, or for at least a third of our patients, longer than 5 years, is that the overall survival curves indicate that we are actually doing an excellent job, as Ridwan alluded to, in selecting patients who are more likely to die of other causes. I think it’s important as we move forward to really try to define those objective criteria to say who the best patients are for active surveillance. How do we safely employ this among other institutions at a population-based level to avoid unnecessary surgery in these patients?

Cancer Network: Lastly, for both of you, what are the next steps in terms of how to care for these patients? Are you following up this study with others?

Alam: The next thing we are looking at are the quality-of-life differences among patients who undergo the different types of interventions like partial nephrectomy, radical nephrectomy, and ablative therapies, and comparing those patients with active surveillance patients. There are other things like kidney function studies that we want to take a look at to see the long-term prognosis for these patients that undergo different management strategies.

Pierorazio: As Ridwan is alluding to, there is more to managing kidney cancer than just survival. We are really trying to look at quality of life and renal function outcomes. I think some of the important data that we will also get to is growth rates. It’s always been the inclination and understanding from retrospective data that growth rates imply biologic behavior of tumors, and I will tell you anecdotally, over the last 7 years, we are really not finding that to be true. We are finding that growth rate is really not predictive of biological behavior and now we are finally amassing the data to support that. I think that will be some really exciting data to come from our group.

Cancer Network: Thank you so much to both of you for joining us today.

Pierorazio: Thank you.

Alam: Thank you.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.