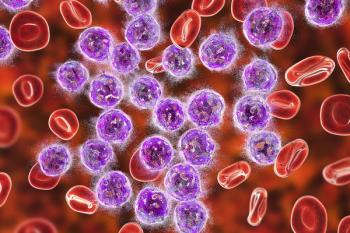

DLBCL Patients Event-Free at 2 Years Survive as Long as General Population

A new study of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) suggests that event-free status at 2 years post-treatment is a useful endpoint both for research and for patient counseling.

A new study of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) suggests that event-free status at 2 years post-treatment is a useful endpoint both for research and for patient counseling. Patients who survived event-free to 2 years have subsequent overall survival similar to that of the general population.

“This study provides evidence-based assessment of the excellent outcome in patients with DLBCL who remain event-free 2 years from diagnosis after standard treatment, and we can quantify this outcome in relation to mortality risk in the general population,” said study lead author Matthew J. Maurer, MS, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, in an email.

The study, results of which were

At the time of diagnosis, patients had a significantly reduced survival compared with age- and sex-matched controls in the general population; the standardized mortality ratio (SMR) was 2.88 (95% CI, 2.51-3.30; P < .001). Those who survived event-free to 12 months saw a reduced SMR, but it was still significantly worse than the general population, at 1.40 (95% CI, 1.10-1.76; P = .0038). Patients who were event-free at 24 months (EFS24), however, had a non-significant SMR of 1.18 (95% CI, 0.89-1.57; P = .25).

“EFS24 is a dichotomous endpoint that identifies disease-related outcome in patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL and may allow us to use earlier endpoints in clinical trials… making the trial process quicker and more efficient,” Maurer said. Traditionally, trials in this disease setting have used time-to-event endpoints, and since therapies are often quite effective this can mean very long and extended trials. The authors also noted that these data call into question the use of routine surveillance imaging for those patients still in remission beyond 24 months.

And the use of EFS24 could be meaningful in daily clinical practice as well. Clinicians, Maurer said, could “reassure patients that achieving EFS24 [means] their overall likelihood of surviving the next 5 years is now essentially the same as it was prior to diagnosis. However, it is important to note that achieving EFS24 does not mean cure.” The authors noted that clinical risk prediction models would be useful to identify patients at higher risk of early relapse.

“Survivorship issues are important in these patients, as they should be sure to resume appropriate preventive medical care or medical maintenance practices when they have achieved this landmark time point without relapse,” Maurer said.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.