- ONCOLOGY Vol 11 No 7

- Volume 11

- Issue 7

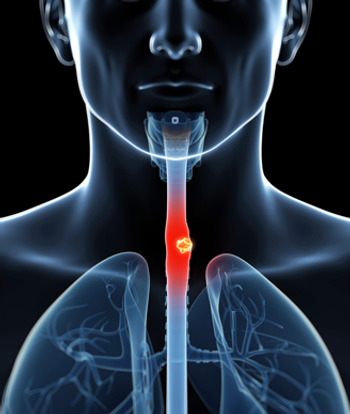

Esophageal Cancer Surgical Practice Guidelines

The Society of Surgical Oncology surgical practice guidelines focus on the signs and symptoms of primary cancer, timely evaluation of the symptomatic patient, appropriate preoperative extent of disease evaluation, and the role of the surgeon in

The Society of Surgical Oncology surgical practice guidelines focuson the signs and symptoms of primary cancer, timely evaluation of the symptomaticpatient, appropriate preoperative extent of disease evaluation, and therole of the surgeon in diagnosis and treatment. Separate sections on adjuvanttherapy, follow-up programs, or management of recurrent cancer have beenintentionally omitted. Where appropriate, perioperative adjuvant combined-modalitytherapy is discussed under surgical management. Each guideline is presentedin minimal outline form as a delineation of therapeutic options.

Since the development of treatment protocols was not the specific aimof the Society, the extensive development cycle necessary to produce evidence-basedpractice guidelines did not apply. We used the broad clinical experienceresiding in the membership of the Society, under the direction of AlfredM. Cohen, MD, Chief, Colorectal Service, Memorial Sloan-Kettering CancerCenter, to produce guidelines that were not likely to result in significantcontroversy.

Following each guideline is a brief narrative highlighting and expandingon selected sections of the guideline document, with a few relevant references.The current staging system for the site and approximate 5-year survivaldata are also included.

The Society does not suggest that these guidelines replace good medicaljudgment. That always comes first. We do believe that the family physician,as well as the health maintenance organization director, will appreciatethe provision of these guidelines as a reference for better patient care.

Symptoms and SignsEarly-stage disease

- Asymptomatic--picked up on routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopyor other investigation

- Dysphagia, odynophagia, anemia, gastrointestinal bleeding

Advanced-stage disease

- Symptoms of locally advanced disease, eg, chest pain, upper abdominalpain, hoarseness or tracheo-esophageal fistula with as- piration pneumonia

- Symptoms of metastatic disease (neurologic, hepatic, bone)

Evaluation of the Symptomatic Patient

Diagnosis

- Barium swallow and upper gastrointestinal (GI) series

- CT scan

- Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

Appropriate timeliness of surgical referral

- Prompt evaluation of patients as described above under "Symptomsand Signs"

Preoperative Evaluation for Extent of Disease

Routine

- Complete history and physical examination

- Chest x-ray

- Barium swallow and upper GI series

- CT scan--chest and upper abdomen (± neck)

- Routine blood chemistries

Further investigations (where indicated by above or optional)

- Endoscopic ultrasound

- Investigation for metastatic disease (bone scan, CT scan, laparoscopy)

Procedures

- Esophagoscopy plus upper GI endoscopy

- Bronchoscopy--for lesions above inferior pulmonary vein

- Laparoscopy and/or thoracoscopy when indicated--to rule out unresectabledisease or widespread metastases

Role of the Surgeon in Management

Preoperative evaluation

- The surgeon is expected to completely evaluate the patient and analyzeall testing that has been done or initiate such testing. This may includea bronchoscopy, esophagoscopy, laparoscopy, and thoracoscopy.

- Cardiorespiratory evaluation

Diagnostic procedures

- The surgeon must be adept at performing all invasive endoscopy proceduresrequired for preoperative evaluation and clinical staging.

Surgical considerations

- The surgeon must be adept at performing partial and total esoph- agectomyutilizing the intra-abdominal, transthoracic, and cervical approaches,as necessary. Esophageal resection margins of at least 5 cm are the goal.The surgeon must be able to utilize the colon or small intestine, as wellas the stomach, for esophageal replacement. The surgeon must be familiarwith upper abdominal and mediastinal lymph node dissection.

- Palliative maneuvers to alleviate dysphagia may include: stent insertion,laser ablation, and esophageal bypass.

These guidelines are copyrighted by the Society of Surgical Oncology(SSO). All rights reserved. These guidelines may not be reproduced in anyform without the express written permission of SSO. Requests for reprintsshould be sent to: James R. Slawny, Executive Director, Society of SurgicalOncology, 85 W Algonquin Road, Arlington Heights, IL 60005.

Although carcinoma of the esophagus is a relatively uncommon malignancy,with an age-adjusted incidence of only 10 cases per 100,000 people in NorthAmerica, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rapidly increasingin patients with chronic reflux disease. This latter tumor is often associatedwith the development of columnar-lined epithelium (Barrett's esophagus).In some areas of the world, eg, northern China, northern Iran, and southernAfrica, squamous cell carcinoma is very common, with an age-adjusted incidenceas high as 150 cases per 100,000 males.

Whereas adenocarcinoma of the esophagus seems to be related to acid-bilereflux disease, squamous cell carcinoma has been associated with Plummer-Vinsonsyndrome in Oriental and black males, as well as Scandinavian females.Heavy alcohol consumption and heavy tobacco intake have been implicatedas cocarcinogens for squamous cell carcinoma. Nutritional factors, suchas high nitrosamine intake and vitamin deficiencies, also have been implicatedin the production of squamous cell disease.

Screening approaches (eg, esophageal cytology, biannual endoscopy) havebeen employed most frequently in high-risk geographic areas (mass screening)and in patients identified with columnar-lined epithelium (individual screeningprogram). In such situations, screening has permitted earlier diagnosisand treatment.

The international TNM staging system has been used to clinically andpathologically stage disease, allowing for the determination of treatmentoptions and ultimate prognosis (Table 1).

The treatment of choice for early-stage carcinoma of the esophagus continuesto be debated. Both surgery and radiotherapy can be used to effect a cure.In early-stage (stage I and II) disease, surgical treatment provides thebest opportunity for local control. Radiotherapy combined with concurrentchemotherapy appears to be superior to radiotherapy alone in the nonsurgicalmanagement of this disease.

The goal of surgical treatment is to effect a complete resection andallow for early resumption of near-normal swallowing. The standard surgicalexcision includes a near-total esophagectomy, regional lymphadenectomy,and a high intrathoracic or cervical anastomosis. The conduit of choicein most instances is the stomach. There is renewed interest in radicaltwo- and three-field lymphadenectomy, as well as wide en bloc resectionof the primary tumor, in order to improve local control and ultimate survival.

Once tumors extend beyond the outer muscle wall or involve more thanfour regional lymph nodes, the chance of curative treatment by surgeryis extremely poor. Preoperative clinical staging, therefore, is extremelyimportant.

In patients with metastases extending beyond the regional lymph nodes,curative surgical treatment is rarely possible and is usually not indicated.In most such patients, only palliative therapy can be offered. Palliativemaneuvers that can improve swallowing include: neodymium:yttrium aluminumgarnet (Nd:Yag) laser destruction of obstructing tumors, insertion of endoesophagealstents, and, on occasion, esophageal exclusion and bypass.

Although the 5-year cure rate of all patients presenting with carcinomaof the esophagus does not exceed 5%, the prognosis for early-stage tumorsis much more optimistic. Early-stage carcinoma of the esophagus (T1, N0)can be cured in up to 70% of patients. Approximately 40% of patients withstage II disease can be cured. More advanced disease decreases survivalfollowing surgical resection to 15% or less .

The role of preoperative (induction) or postoperative (adjuvant) chemotherapyor chemoradiation in the treatment of patients with esophageal cancer isstill being investigated. Although reported trials suggest that postoperativechemotherapy and/or radiotherapy have very little impact on overall survival,encouraging phase II and III data suggest that induction chemotherapy orchemoradiation prior to surgery may improve survival. However, this requiresconfirmation in very large prospective, randomized trials.

In early in situ disease, the role of mucosectomy and argon beam laserdestruction with photoexcitation is being investigated as a possible alternativeto esophagectomy.

References:

Akiyama H: Surgery for Cancer of the Esophagus. Baltimore, Williamsand Wilkins, 19xx..

Altorki NK, Skinner DB: Adenocarcinoma in Barrett's esophagus. SeminSurg Oncol 6:274, 1990.

Blot WJ, Devesa SS, Kneller RW, et al: Rising incidence of adenocarcinomaof the esophagus and gastric cardia. JAMA 265:1287, 1991.

Dent J, Bremner CG, Collen MJ, et al: Barrett's esophagus. J GastroenterolHepatol 6:1, 1991.

Earlam RJ, Cunha-Melo JR: Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: I. Acritical review of surgery. Br J Surg 67:381, 1980.

Earlam RJ, Johnson L: 101 oesophageal cancers: A surgeon uses radiotherapy.Ann R Coll Surg Eng 72:32, 1990.

Herskovic A, Martz K, Al-Sarraf M, et al: Combined chemotherapy andradiotherapy compared to radiotherapy alone in patients with cancer ofthe esophagus. N Engl J Med 326:1593, 1992.

Huang GJ, Zhang DW, Wang GQ, et al: Surgical treatment of carcinomaof the esophagus: a report of 1647 cases. Chin Med J 94:305, 1981.

Lewis I: The surgical treatment of carcinoma of the esophagus with specialreference to a new operation for growths of the middle third. Br J Surg34:18, 1946.

Li JY: Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in China. Natl Can Instit Monogr62:121-122, 1982.

McKeown KC: Carcinoma of the oesophagus. J R Coll Surg Edinb 24:253,1979.

Pearson FG, Deslauriers J, Ginsberg RJ, et al (eds): Esophageal Surgery.New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1995.

Putman Jr., Suell DA, Natarajan G, et al: A comparison of three techniquesof esophagectomy for carcinoma of the esophagus from one institution witha residency training program. Ann Thorac Surg 57:319-325, 1994.

Teniere P, Hay JM, Fingerhut A, Fagniez PL (French University Associationfor Surgical Research): Postoperative radiation therapy does not increasesurvival after curative resection for squamous cell carcinoma of the middleand lower esophagus, as shown by a multicenter controlled trial. Surg GynecolObstet 173:123, 1991.

Thames HD, Peter LJ, Withers HR, et al: Accelerated fractionation vshyperfractionation rationales for several treatment per day. Int J RadiatOncol Biol Phys 9:127, 1983.

Wong J: Esophageal resection for cancer: The rationale of current practice.Am J Surg 153:18, 1987.

Articles in this issue

over 23 years ago

Chromosomal Abnormalities Predict Poor Outcome in Multiple Myelomaover 28 years ago

Tumor Board Conference from the University of Pittsburghover 28 years ago

Role of Diet in Cancer Hard to Study, Expert Saysover 28 years ago

Results of Newer Radiation Treatments for Prostate Cancerover 28 years ago

New Evidence That NSAIDs Reduce Breast Cancer Riskover 28 years ago

Book Review: Tamoxifen: A Guide for Clinicians and Patientsover 28 years ago

Pancreatic Cancer Surgical Practice GuidelinesNewsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.