Oncology NEWS International

- Oncology NEWS International Vol 15 No 7

- Volume 15

- Issue 7

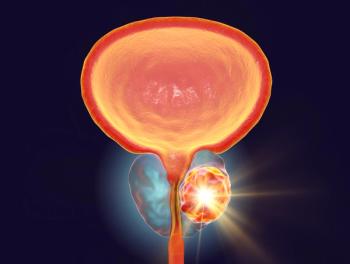

Long Follow-up Shows Surgery Benefits in Localized Prostate Ca

In some men with clinically localized prostate cancer, prostatectomy is associated with a survival advantage, according to results of two long-term studies presented at the 2006 Annual Meeting of the American Urological Association.

ATLANTAIn some men with clinically localized prostate cancer, prostatectomy is associated with a survival advantage, according to results of two long-term studies presented at the 2006 Annual Meeting of the American Urological Association.

After an average follow-up of 11.8 years in the first study (abstract 652), surgery provided a survival advantage over radiation therapy or observation after adjusting for confounding factors. Radiation therapy appeared to provide little or no benefit over observation. "Data from randomized trials initiated in the PSA era are just unavailable to compare outcomes from surgery, radiation, or observation, yet these are the treatment options that many men have to face," said Peter C. Albertsen, MD, University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington.

Dr. Albertsen's retrospective population-based study evaluated 1,618 men diagnosed in Connecticut from 1990 to 1992. The investigators analyzed overall survival, cancer-specific survival, and case fatality rates during the 13 years after surgery (n = 802), external beam radiation (n = 702), or observation (n = 114). Patients receiving surgery were younger than those who received radiation or observation, with a median age in each treatment arm of 65, 71, and 70 years, respectively, and they had fewer comorbidities.

Among the patients treated with surgery, 8% died of prostate cancer vs 18% of the radiation patients and 16% of those who were observed. The survival benefit with surgery was seen in patients with low-, intermediate-, and high-risk disease based on D'Amico risk category.

Dr. Albertsen noted that today's patient populations differ from the study cohort due to repeated PSA testing. Moreover, this study is subject to the limitations of a retrospective analysis. He also mentioned that methods of radiation have improved since the early 1990s when the procedures in this study were done.

The other long-term study (abstract 646) evaluated survival during a median follow-up of 22 years after surgery for localized prostate cancer. The cohort included 849 men who underwent radical prostatectomy between 1971 and 1984, and 767 watchful waiting patients.

Prostatectomy provided a survival advantage over watchful waiting in men with intermediate- and high-grade tumors (Gleason score of at least 6) at each age group tested (55-59 up to 70-74 at diagnosis). Men continued to die of prostate cancer many years after treatment. "Many patients die of prostate cancer even 15, 20, and up to 25 years after being treated. So studies with shorter follow-up simply are missing many of the events," said Brant A. Inman, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

Compared with the surgery patients, the watchful waiting cohort was older (median age, 69 vs 65) and had more comorbidities (24% vs 11% with Charlson score 2+). However, the prostatectomy patients appeared to have more severe disease than the watchful waiting cohort, according to the proportion diagnosed with biopsy (87% vs 26%), proportion with elevated acid phosphatase (89% vs 47%), and clinical stage (proportion with cT2, 75% vs 15%). Moreover, 24% of these patients had positive nodes. The investigators saw little age effect on the NNT (number needed to treat), determined for each age group and biopsy Gleason score. Moreover, only half of patients with PSA recurrence died from prostate cancer. As with the other long-term study, these results should be considered in the context of the pre-PSA era in which the men were diagnosed and treated, Dr. Inman said.

Articles in this issue

over 19 years ago

High-Quality Screening Colonoscopy Priority for GI Docsover 19 years ago

Genentech Seeks Expanded Use of Avastin in Breast Cancerover 19 years ago

Denosumab Suppresses Bone Resorption in Breast Ca Metsover 19 years ago

FDA Approves Priority Review of Merck's Zolinza (Vorinostat)over 19 years ago

FDA Approves Revlimid for Myeloma Rxover 19 years ago

Real-Time RT Planning, Delivery in the Bronxover 19 years ago

Phase III Trial of Enzastaurin for NHL Patients Initiatedover 19 years ago

Racial Disparities in Prostate Ca RecurrenceNewsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.