Post-Surgical Relapse Patterns in High-Risk Non–Clear Cell RCC

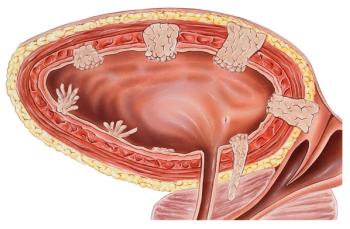

Cross-sectional, long-term imaging is shown to be important for patients with high-risk resected non–clear cell RCC.

Patients with non–clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) had a distinct pattern of relapse compared with patients with clear cell disease, according to the results of a recent study.

Because non–clear cell RCC makes up such a small percentage of the total diagnosed RCCs, optimal management of patients with non–clear cell RCC is unclear. Typically, these patients are treated based on evidence taken from well-established clear cell RCC treatment regimens.

“Our

According to Narayan and colleagues, the natural history of non–clear cell RCC after curative surgery remains poorly defined. To gain a better understanding of relapse patterns in these patients, the researchers conducted a retrospective study of patients with non–clear cell RCC enrolled in a large randomized trial of adjuvant antiangiogenic therapy for high-risk RCC.

In the phase III ECOG-ACRIN E2805 trial, the researchers included data from 403 patients with non–clear cell RCC. These patients were treated with up to 54 weeks of postoperative sunitinib, sorafenib, or placebo, and had surveillance imaging at standardized intervals. Sixty-three percent of patients underwent an open surgical approach, and 93% had radical nephrectomy.

During the follow-up period, about one-third of tumors (36%) recurred at a median of 6.2 years. Five-year recurrence risks were similar between those patients with non–clear cell RCC and 1,541 patients with clear cell histology (34.6% vs 39.5%).

Those patients with non–clear cell RCC had an increased risk for abdominal sites of relapse (26.4% vs 18.2%; P = .0008). Among the sites of abdominal recurrences were lymph nodes (39%), nephrectomy bed (17%), and liver (13%).

“The apparent increased rate of abdominal site relapse with non–clear cell RCC raises the hypothesis of potential benefit from intensified abdominal surveillance and/or consideration of additional local therapy,” the researchers wrote. “In addition, intensified abdominal surveillance may allow for the identification of disease relapse at earlier stages, therefore potentially enabling metastasectomy or other local salvage therapies.”

In contrast, patients with non–clear cell RCC were less likely to relapse in the chest (13.7% vs 20.9%; P = .0005).

There were no differences observed for sites of relapse and histology based on the type of adjuvant treatment patients received.

Overall, the researchers concluded that because as many as 90% of clinical recurrences would have been detected using strict adherence to American Urological Association and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, the “current guidelines are largely adequate,” but these new data “emphasize the importance of long-term follow-up beyond 5 years in order to capture approximately 10% of observed late non–clear cell RCC recurrences.”

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.