Researchers Call for More Conservative Treatment of Small Thyroid Cancers

The steep increase in thyroid cancer diagnosis has not been mirrored by increasing mortality rates and is likely due to widespread overdiagnosis of small neoplasms.

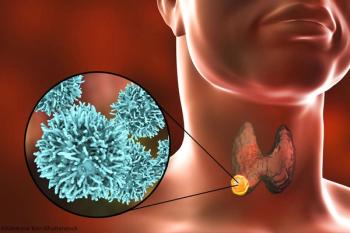

The incidence of thyroid cancer diagnosis has tripled since the early 1990s, with 50,000 Americans expected to be newly diagnosed this year-but that steep increase has not been mirrored by increasing mortality rates and is likely due to widespread overdiagnosis of small (≤ 2 cm) preclinical papillary thyroid neoplasms, researchers

They called for restraint in fine-needle biopsy of small thyroid nodules and “de-intensified” medical interventions, including more reliance on active surveillance for selected patients with small papillary thyroid neoplasms.

When patients do wish to remove small thyroid tumors, thyroid lobectomy, leaving half of the thyroid gland to maintain thyroid function, should be done whenever possible instead of total thyroidectomy, argued coauthors

Currently, 80% of patients who receive surgery for thyroid cancer undergo total thyroidectomy, even though this necessitates lifelong thyroid hormone replacement therapy. But the 25-year risk of mortality is “extremely low” (2%) for patients with small papillary thyroid tumors, and partial lobectomy surgery survival rates are comparable to those for total thyroidectomy.

“The average age of diagnosis for thyroid cancer is 50 [years],” Welch noted in a press release. “So, potentially, someone could live up to half of their life with the effects-both physical and psychological-of these treatments. That’s something we need to take very seriously.”

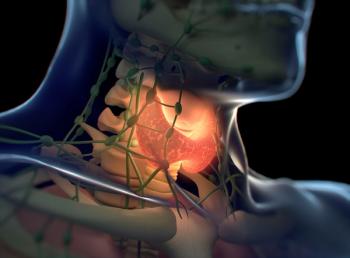

Patient education and decision-making discussions should include clear communication of the fact that many small thyroid cancers never progress to become life threatening. All adults, and particularly those age 60 or older at diagnosis, are candidates for active surveillance if their small papillary

But the clinical evidence base on the risks and benefits of active surveillance and nonsurgical management of small thyroid cancers is small, cautioned

“Most of the evidence consists of case series in the Japanese literature,” Megwalu noted. “There are currently no defined criteria for determining who is appropriate for observation.”

The Japanese researchers restrict surveillance to patients with “micro” carcinomas of the thyroid smaller than 1 cm in diameter and without high-risk features, he noted.

Moreover, in 2015, the American Thyroid Association (ATA) updated its 2009-released thyroid cancer management

Welch and Doherty’s analysis only includes data through 2014, Megwalu noted, and therefore does not reflect the impact of the 2015 ATA guidelines on surgery rates.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.