- ONCOLOGY Vol 11 No 9

- Volume 11

- Issue 9

Soft-Tissue Sarcoma Surgical Practice Guidelines

The Society of Surgical Oncology surgical practice guidelines focus on the signs and symptoms of primary cancer, timely evaluation of the symptomatic patient, appropriate preoperative evaluation for extent of disease, and role of the surgeon in diagnosis and treatment. Separate sections on adjuvant therapy, follow-up programs, or management of recurrent cancer have been intentionally omitted. Where appropriate, perioperative adjuvant combined-modality therapy is discussed under surgical management. Each guideline is presented in minimal outline form as a delineation of therapeutic options.

The Society of Surgical Oncology surgical practice guidelines focuson the signs and symptoms of primary cancer, timely evaluation of the symptomaticpatient, appropriate preoperative evaluation for extent of disease, androle of the surgeon in diagnosis and treatment. Separate sections on adjuvanttherapy, follow-up programs, or management of recurrent cancer have beenintentionally omitted. Where appropriate, perioperative adjuvant combined-modalitytherapy is discussed under surgical management. Each guideline is presentedin minimal outline form as a delineation of therapeutic options.

Since the development of treatment protocols was not the specific aim ofthe Society, the extensive development cycle necessary to produce evidence-basedpractice guidelines did not apply. We used the broad clinical experienceresiding in the membership of the Society, under the direction of AlfredM. Cohen, MD, Chief, Colorectal Service, Memorial Sloan-Kettering CancerCenter, to produce guidelines that were not likely to result in significantcontroversy.

Following each guideline is a brief narrative highlighting and expandingon selected sections of the guideline document, with a few relevant references.The current staging system for the site and approximate 5-year survivaldata are also included.

The Society does not suggest that these guidelines replace good medicaljudgment. That always comes first. We do believe that the family physician,as well as the health maintenance organization director, will appreciatethe provision of these guidelines as a reference for better patient care.

Symptoms and Signs

- Painless mass growing for a variable length of time

- Mass after an injury that does not rapidly resolve

Evaluation of the Symptomatic Patient History and physical examination

- Comprehensive history and physical examinationpersonal or family historyof malignancy or genetic disease

- Nature and duration of symptoms

- Prior exposure to chemical toxins or radiation

Extremities

- Assess the mobility of the mass vs fixity to deep structures.

- Assess the size, depth, and consistency of the mass.

- Ascertain clinical involvement of overlying skin or regional lymphnodes.

- Examine motor and sensory nerve function.

- Examine for swelling distal to the mass or for any ecchymosesoverlyingthe mass.

- Radiologic and laboratory studies

- MRI

Pelvis/retroperitoneum

- Difficult to evaluate on physical examination. However, flank bulgingor mass effect on deep abdominal palpation should be evaluated further.

- Pelvic or rectal examination may raise the possibility of anunderlyingsoft-tissue sarcoma.

- Radiologic and laboratory studies

- Radiologic studies should be performed prior to biopsy.

- MRIextremity

- CTpelvis, abdomen, retroperitoneum

- Celiac axis arteriogram in selected patients with visceral sarcoma

- CBC, chemistry profile, and chest x-ray

Biopsy

- Incision oriented parallel to the long axis of extremity

- Core needle biopsy for superficial lesions

- Needle aspiration if cytopathology expertise available

- Excisional biopsy is reserved for extremity lesions £3 cm.

Appropriate timeliness of surgical referral

- Soft-tissue sarcoma can grow rapidly and disseminate: therefore, thework-up and biopsy should be performed expeditously in the presence ofthe above symptoms or signs.

Preoperative Evaluation for Extent of Disease Physical examination Chest CT

- Obtain chest CT in addition to primary tumor imaging and routine studiesin patients with lesions > 5 cm, grade II or III.

CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis in selected patients

- Myxoid liposarcomas ³ 5 cm have tendencyto metastasize to themediastinum, root of the mesentery, and retroperitoneum.

CT scan of the head in selected patients

- Alveolar soft-part sarcoma may metastasize selectively to the cen

tral nervous system.

Liver ultrasound or abdominal CT

- Patients with intra-abdominal, genitourinary, or retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomahave a marked tendency to develop liver metastases.

MRI

- As discussed above

Role of the Surgeon in Initial Management Preoperative evaluation

- The initial evaluation and diagnostic work-up should be coordinatedby the surgeon who will perform the definitive operation.

- Radiotherapy and chemotherapy treatments should be considered onlyafter the diagnostic work-up is completed.

Surgical considerations

- Surgeon must be able to perform wide local excisions in combinationwith interstitial or postoperative radiotherapy.Accurate intraoperativesurgical field delineation is critical.

- In patients who have received preoperative radiotherapy, the sarcomasurgeon must be capable of resecting disease and managing wounds in anirradiated field.

- Radical amputation in selected patients with extremity sarcoma

- Radical multiorgan/vascular/orthopedic resections for selected in tra-abdominal/retroperitonealsarcoma

These guidelines are copyrighted by the Society of Surgical Oncology(SSO). All rights reserved. These guidelines may not be reproduced in anyform without the express written permission of SSO. Requests for reprintsshould be sent to: James R. Slawny, Executive Director, Society of SurgicalOncology, 85 West Algonquin Road, Arlington Heights, IL 60005.

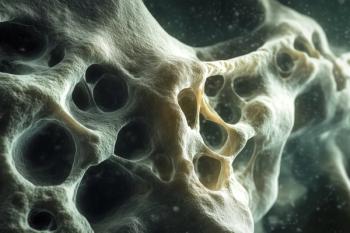

Soft-tissue sarcomas are tumors of putative mesodermal origin thatdevelop in the extraskeletal connective tissues. These tumors constitute< 1% of adult malignancies and approximately 7% of pediatric malignancies,and have an annual age-adjusted incidence of 2 cases per 100,000 population.[1]Approximately 6,300 new cases of soft-tissue sarcoma and 3,100 deaths arereported annually in the United States.[2]

Sarcomas occur most commonly in the extremity in adults and in the headand neck in children. Overall, approximately 50% of soft-tissue sarcomasoccur in the extremities, 10% in the head and neck, and 40% in the trunkand retroperitoneum.

There is little evidence to suggest a genetic predilection to the developmentof soft-tissue sarcomas other than in Li-Fraumeni kindreds, in whom p53tumor-suppressor gene mutations also create a predisposition to breastcarcinoma and a variety of other malignancies. Soft-tissue sarcomas alsooccur with greater frequency in patients with several other genetic diseases,including basal cell nevus syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, Werner's syndrome,Gardner's syndrome, and von Recklinghausen's disease (patients with vonRecklinghausen's disease, for example, have a 10% likelihood of ultimatelydeveloping a neurofibrosarcoma).[1]

Environmental factors have not been convincingly demonstrated as relevantto the etiology of soft-tissue sarcoma in humans. However, 3-methylcholanthreneand several viruses have been implicated as etiologic factors in experimentalanimal studies. There is no demonstrable connection between retained foreignbodies or antecedent trauma and the subsequent development of soft-tissuesarcoma, although previous exposure to ionizing radiation and chronic lymphedemaare predisposing factors. In this latter context, however, the mostcommon histology is extraskeletal osteosarcoma followed by malignant fibroushistiocytoma.

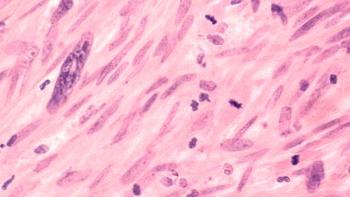

Sarcomas are classified by histology as well as grade. The histologicclassification seeks to ascribe a putative cell of origin for the tumor.Overall, malignant fibrous histiocytoma is the most common subtype (40%of the total), followed by liposarcoma (25%).

Grade assignment is made on the basis of the number of mitoses per high-poweredmicroscopic field, nuclear morphology, degree of cellularity, cellularanaplasia, degree of necrosis, or other criteria that vary from centerto center.[3] Unfortunately, light microscopic determination of histopathologyand grade are imprecise, and discordancy rates as high as 40% have beenobserved prospectively, even among expert sarcoma pathologists.[4]

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system (Table1) is most commonly applied in soft-tissue sarcoma for prognostic andtherapeutic purposes, although alternative staging systems have been proposed,including those of the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society and the Memorial Sloan-KetteringCancer Center. The AJCC system uses the four criteria of tumor, nodal status,grade, and metastasis (TNGM) to assign one of four disease stages.

Overall, tumor size and grade are the most important determinants ofprognosis.[3] About two-thirds of all sarcomas are high-grade lesions.Newer information suggests that the prognostic risk for disseminated diseaseis most dependent on the histopathologic grade in the first 2 or 3 years,but after that the size of the initial lesion becomes at least as importantas grade. The overall incidence of nodal metastasis is < 3% and is thereforeminimally relevant to prognosis in most patients.[5]

Extremities

Stage I tumors are low-grade lesions of any size and are generally treatedby wide local excision. The addition of radiotherapy is dictated by tumorsize and anatomic constraints to a resection with negative margins.[6]

Stage II tumors are intermediate-grade tumors of any size that are usuallytreated by surgery in combination with radiotherapy.[6] Use of chemotherapyis generally reserved for stage II patients with recurrent disease or patientswho need tumor cytoreduction prior to resection with limb sal

vage intent.[7]

Stage III lesions are high-grade lesions of any size that have not developedregional or distant metastases. High-grade tumors > 5 cm diameter havethe greatest tendency to metastasize and are treated by surgery in conjunctionwith radiotherapy. Many patients with these tumors are also eligible forprospective clinical trials of neoadjuvant or adjuvant multidrug chemotherapy.[7,8]

The two drugs with the greatest activity in soft-tissue sarcoma aredoxorubicin and ifosfamide (Ifex). However, overall response rates in thebest multimodality protocols are only 40% to 60%. Toxicities of chemotherapyare significant and include permanent cardiac muscle damage, transienturothelial injury, and temporary, although potentially life-threatening,myelosuppression.[7,8] Because of these serious toxicities, systemic chemotherapyfor soft-tissue sarcoma should be administered only in prospective trials,in which strict criteria for enrollment and follow-up monitoring can bemaintained.

Chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment for stage IV disease (ie,soft-tissue sarcomas with regional or metastatic spread). In stage IV disease,surgery or radiotherapy is usually used solely for palliation. Surgerywith curative intent is generally impossible in patients with stage IVdisease; the only exception is pulmonary metastasis, for which curativemetastatasectomy is possible in selected patients undergoing complete resectionof the primary tumor.[9]

Radiotherapy can be administered by external beam preoperatively[10]or postoperatively[11] or, alternatively, as a postoperative interstitialimplant (brachytherapy).[12] These various radiotherapy approaches havenever been directly compared in prospective, randomized trials.

Preoperative radiotherapy requires approximately 50 Gy to achieve tumorcontrol, which is comparable to the 65-Gy dose required for local controlif radiotherapy is given postoperatively. The increased postoperative doseis necessitated by the hypoxic postoperative wound environment, which alsomandates a wider radiotherapy field extending beyond the area of surgicalresection. However, postoperative radiotherapy avoids the significant woundhealing problems of preoperative radiation, the incidence of which approaches30% in some series.[13]

Brachytherapy results in local control rates comparable to either preoperativeor postoperative external-beam radiotherapy (7% to 15% rate of local recurrencefor surgery with definitive radiotherapy in most series).[12] In addition,brachytherapy is usually much more convenient for patients and appearsto be less expensive. Unlike external-beam radiation, there is minimalscatter radiation with brachytherapy, making this technique optimal fortumors near open epiphyseal plates, gonads, and other structures particularlyvulnerable to radiation toxicity.

Retroperitoneum

Soft-tissue sarcomas of the retroperitoneum pose a special challengebecause they frequently grow to a large size before causing symptoms. Consequently,resection can be difficult (50% to 60% rate of resectability in most series).[14]Central anatomic tumor involvement of the celiac axis, root of the mesentery,great vessels, or porta hepatis usually precludes resection.

The liver and lungs are equally frequent sites of metastasis from primaryretroperitoneal sarcomas. Complete surgical resection is the primary determinantof survival in patients with hepatic metastases; however, hepatic metastasectomyhas not been proven to be of value.[15]

In the retroperitoneum, no prospective randomized trials have demonstratedimproved overall survival using chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy adjuvantlyor neoadjuvantly, although intraoperative radiotherapy may decrease localrecurrence.[16]

Survival in soft-tissue sarcomas is driven by the reality that almost80% of metastases are to the lungs and that these usually occur within2 to 3 years of initial diagnosis. A 30% survival rate at 3 years can beanticipated if the pulmonary metastases are resectable.[9]

Size, grade, surgical margins, depth of tumor, anatomic location, andprevious surgery are all important determinants of outcome. However, thesefactors have a variable impact on specific survival measures, such as overallsurvival, disease-free survival, local recurrence, and distant disease-freesurvival; ie, the prognostic factors predictive of local recurrence differfrom those predictive of distant metastases and overall survival.

Unlike some tumor systems, local recurrence of soft-tissue sarcoma isnot necessarily a harbinger of uncontrollable distant failure. Therefore,local recurrence should be treated aggressively to preserve the highestquality of life for the patient. Long-term follow-up is required becauselate recurrence is noted in up to 10% of patients after 5 years.

Patient-based outcomes research, which differs from physician-definedsurvival research, is still in its infancy for soft-tissue sarcoma. Inthe future, treatments will be assessed for their impact on survival, cost,and effect on quality of life as a means to maximize overall efficacy.These latter considerations will appropriately assume increasing importanceas the percentage of soft-tissue sarcoma patients achieving long-term cureincreases beyond the current 50% plateau level.

References:

1. Yang JC, Glatstein EJ, Rosenberg SA, et al: Sarcomas of the softtissues, in DeVita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA (eds): Cancer Principles& Practice of Oncology, 4th ed. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, 1993.

2. Lawrence W, Donegan WL, Nachimuth N, et al: Adult soft tissue sarcomas:A pattern of care survey of the American College of Surgeons. Ann Surg205:349-359, 1987.

3. Gaynor JJ, Tan CC, Casper ES, et al: Refinement of clinicopathologicstaging for localized soft tissue sarcoma of the extremity: A study of423 adults. J Clin Oncol 10:1317-1329, 1992.

4.Alvegard TA, Berg NO: Histopathology peer review of high-grade softtissue sarcoma: The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group experience. J Clin Oncol7:1845-1851, 1989.

5. Fong Y, Coit DG, Woodruff JM, et al: Lymph node metastasis from softtissue sarcoma in adults. Ann Surg 217: 72-77, 1993.

6. Geer RJ, Woodruff J, Casper ES, et al: Management of small soft-tissuesarcoma of the extremity in adults. Arch Surg 127: 1285-1289, 1992.

7. Pezzi CM, Pollock RE, Evans HL, et al: Preoperative chemotherapyfor soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities. Ann Surg 211:476-481,1990.

8. Bramwell V, Rouesse J, Steward W, et al: Adjuvant CYVADIC chemotherapyfor adult soft tissue sarcomareduced local recurrence but no improvementin survival: A study of the European Organization for Research and Treatmentof Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. J Clin Oncol 12:1137-1149, 1994.

9. Putnam JB, Roth JA: Resection of sarcomatous pulmonary metastases.Surg Clin North Am 2:673-691, 1993.

10. Barkley HT, Martin RG, Romsdahl MM, et al: Treatment of soft tissuesarcomas by preoperative irradiation and conservative surgical resection.Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 14:693-699, 1988.

11. Lindberg RD, Romsdahl MM, Barkley HT: Conservative surgery and postoperativeradiotherapy in 300 adults with soft-tissue sarcomas. Cancer 47:2391-2397, 1981.

12. Harrison LB, Franzese F, Gaynor JJ, et al: Long-term results ofa prospective randomized trial of adjuvant brachytherapy in the managementof completely resected soft tissue sarcomas of the extremity and superficial trunk. Int J Radiat Oncol BiolPhys 27:259-265, 1993.

13. Bujko K, Suite HD, Springfield DS, et al: Wound healing after preoperativeradiation for sarcoma of soft tissues. Surg Gynecol Obstet 176:124-134,1993.

14. Jacques DP, Coit DG, Hajdu SI, et al: Management of primary andrecurrent soft tissue sarcoma of the retroperitoneum. Ann Surg 212:51-59,1990.

15. Jacques DP, Coil DG, Casper ES, et al: Hepatic metastases from soft-tissuesarcoma. Ann Surg 221:392-397, 1995.

16. Sindelar WF, Kinsella TJ, Chen PW et al: Intraoperative radiotherapyin retroperitoneal sarcomas. Arch Surg 123:402-410, 1993.

Articles in this issue

over 28 years ago

UFT: East Meets West in Drug Developmentover 28 years ago

Rationale for Phase I Study of UFT Plus Leucovorin and Oral JM-216over 28 years ago

Postoperative Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancerover 28 years ago

UFT in Gastric Cancer: Current Status and Future Developmentsover 28 years ago

Oral UFT and Leucovorin in Patients With Advanced Gastric CarcinomaNewsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.