Tremelimumab No Match vs Metastatic Melanoma Standard of Care

The anti–cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) antibody tremelimumab failed to achieve a significant improvement in survival among patients with metastatic melanoma compared with the standard of care treatments used in the comparator arm, according to the results of a phase III study.

The anti–cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) antibody tremelimumab failed to achieve a significant improvement in survival among patients with metastatic melanoma compared with the standard of care treatments used in the comparator arm, according to the results of a phase III study.

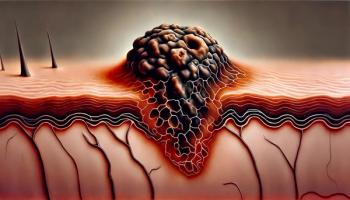

Human melanoma; magnification ×130; scanning electron microscopy

Tremelimumab had shown activity and durable response in this patient population in phase II studies; however, no difference in overall survival was seen in the study results,

“Tremelimumab is an anti–CTLA-4 antibody, which in phase I and II testing had similar clinical effects [to ipilimumab] in terms of response rates and side effects,” said Antoni Ribas, MD, of the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Ipilimumab (Yervoy) is also an anti–CTLA-4 antibody, which was approved for the treatment of metastatic melanoma in March.

This open-label trial included 655 patients with treatment-naive, unresectable metastatic melanoma. Patients were randomly assigned to treatment with 15 mg/kg of tremelimumab every 90 days or physician’s choice of chemotherapy with temozolomide or dacarbazine.

A data safety monitoring committee stopped the trial at the second interim analysis after 340 deaths had occurred. At that time, the median overall survival was 11.8 months for patients assigned tremelimumab vs 10.7 months for those in the standard treatment arm. At the final survival analysis, performed at 534 deaths, median overall survival for tremelimumab was 10.3 months compared with 10.7 months in the standard treatment arm.

“In this study, tremelimumab did not improve overall survival compared to dacarbazine or temozolomide,” Ribas said. “There are several potential explanations, but the most important one is that there was a relatively high rate of patients in the chemotherapy control arm that went on to receive ipilimumab.”

According to the study, 66% of patients (n = 217) in the standard treatment arm reported subsequent therapy, with 46 patients having received ipilimumab.

Although the two physician’s choice medications chosen at trial design were considered standard of care, since that time, the anti–CTLA-4 ipilimumab and the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib (Zelboraf) have both been approved for the treatment of metastatic melanoma.

Ipilimumab was approved based on results from two trials in which the drug demonstrated improved overall survival. The first trial compared ipilimumab with a peptide vaccine; the second combined the drug with the chemotherapy agent dacarbazine and compared the combo to dacarbazine alone.

In their discussion of the results, Ribas and colleagues write that this trial’s open-label design resulted in unintended crossover in the control arm to ipilimumab.

“In contrast, patients in the control groups of ipilimumab randomized phase III studies were excluded from all tremelimumab and ipilimumab trials and from the ipilimumab expanded-access program,” they wrote. “Use of CTLA-4 blockade in both arms of this study could have decreased the power of the study to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in survival and biased the estimates of survival in the control arm.”

Antoni Ribas has received research funding from and has served as a consultant for Pfizer, the manufacturer of tremelimumab. He has also served as a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, the manufacturer of ipilimumab.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.