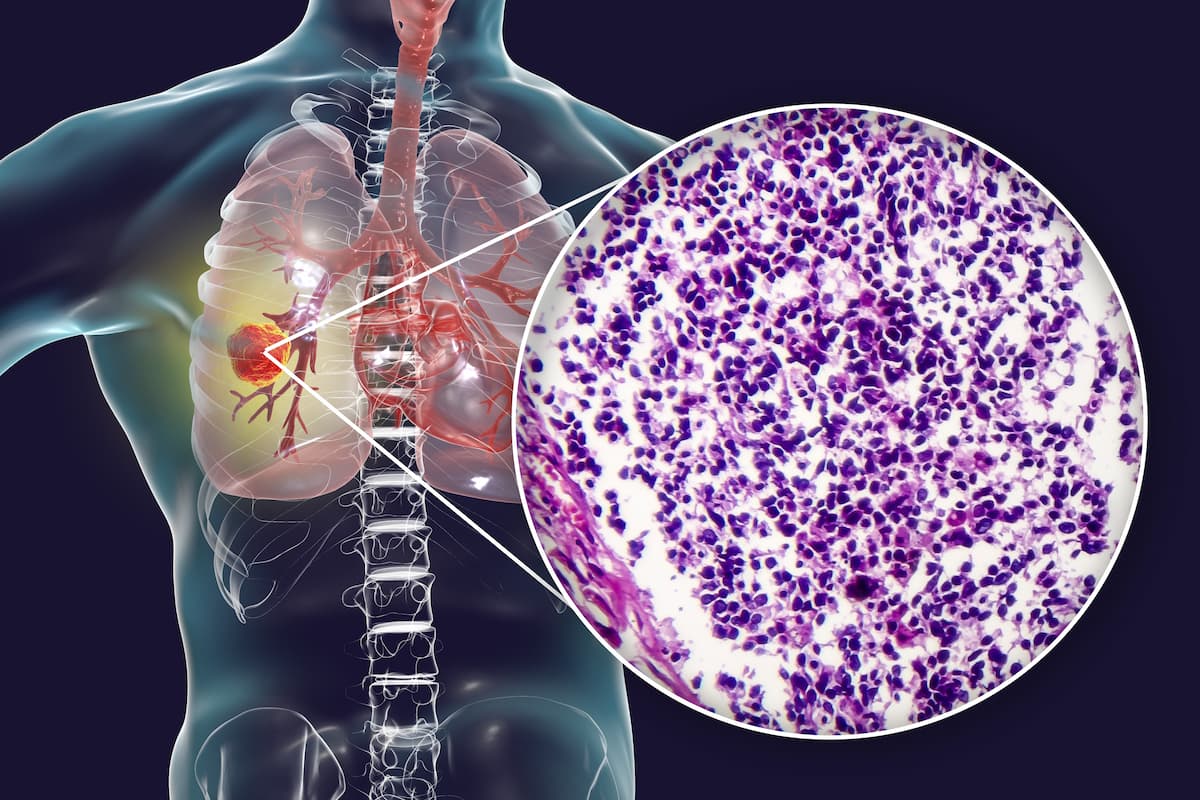

FDA Grants Accelerated Approval to Adagrasib for KRAS G12C–Mutated NSCLC

Patients with KRAS G12C–mutated non–small cell lung cancer can now receive adagrasib therapy following the treatment’s recent accelerated approval by the FDA.

Adagrasib (Krazati) has been granted accelerated approval by the FDA for patients with KRAS G12C–mutated non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), as determined by an FDA-approved test, according to a press release by the FDA.1

The FDA based its approval on the results of the phase 2 KRYSTAL-1 trial (NCT03785249), which was presented at the

“The approval of adagrasib for KRAS G12C–mutated NSCLC will open up another therapeutic option,” Alexander I. Spira, MD, PhD, FACP, a medical oncologist and co-director of the Virginia Cancer Specialists Research Institution, and director of the Thoracic and Phase I Program and clinical assistant professor at Johns Hopkin, said in an interview with CancerNetwork® ahead of the approval. “We already have sotorasib [Lumakras] readily approved, but they do have slightly different toxicity profiles. It's always good to have more than one class because some people do tolerate one better than the other.”

Efficacy was evaluated in 112 patients with NSCLC harboring a KRAS G12Cmutation. They were given 600 mg capsules of adagrasib twice a day. The efficacy of the treatment was assessed based on the primary end point of ORR along with the secondary end points of DOR, progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and safety.

According to a data readout in at the 2022 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, among patients treated with adagrasib monotherapy, 42% achieved a partial response and 37% had stable disease. Of the evaluable patients who had a scan approximately 6 weeks into treatment, the ORR was 51% (n = 48/95). The disease control rate (DCR) was 80%.

The median time in therapeutic range (TTR) was 1.4 months (range, 0.9-7.2). Additionally, the median PFS was 6.5 months (95% CI, 4.7-8.4).

The median OS of patients was 12.6 months (95% CI, 9.2-19.2). Moreover, the 6-month OS rate was 71% (95% CI, 61.1-78.3), and the 12-month rate was 51% (95% CI, 40.9-60.0).

Of 33 radiographically evaluable patients with adequately treated and stable central nervous system (CNS) metastases in the trial, the intracranial (IC) ORR observed was 33%. Five patients within this subgroup achieved complete responses, 6 experienced partial responses, and 17 had stable disease. Additionally, the IC DOR was 11.2 months (95% CI, 3.0-NE), the DCR was 85%, and the median PFS was 5.4 months (95% CI, 3.3-11.6).

The most adverse effects included diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, vomiting, musculoskeletal pain, hepatotoxicity, renal impairment, dyspnea, edema, decreased appetite, cough, pneumonia, dizziness, constipation, abdominal pain, and QTc interval prolongation. Moreover, frequently observed laboratory abnormalities included decreased lymphocytes, increased aspartate aminotransferase, decreased sodium, decreased hemoglobin, increased creatinine, decreased albumin, increased alanine aminotransferase, increased lipase, decreased platelets, decreased magnesium, and decreased potassium.

References

- FDA grants accelerated approval to adagrasib for KRAS G12C-mutated NSCLC. News release. FDA. December 12, 2022. Accessed December 13, 2022. https://bit.ly/3UUVphS

- Spira AI, Riely GJ, Gadgeel SM, et al. KRYSTAL-1: Activity and safety of adagrasib (MRTX849) in patients with advanced/metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring a KRASG12C mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 16): 9002-9002. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.9002

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.