- ONCOLOGY Vol 10 No 8

- Volume 10

- Issue 8

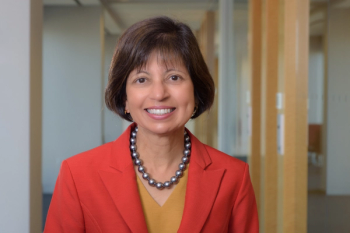

Immunologists Share Alfred P. Sloan, Jr., Prize for Outstanding Contributions to Cancer Research

dvances in cell biology and basic science are made in step-by-step increments of understanding, achieved over years of painstaking research. While not usually typical headline-grabbing material, such research has led to some of the most important

dvances in cell biology and basic science are made in step-by-stepincrements of understanding, achieved over years of painstakingresearch. While not usually typical headline-grabbing material,such research has led to some of the most important medical achievementsof this century, including the development of vaccines that haveeradicated once common and deadly diseases. Scientists have longbeen hoping to develop such vaccines against cancer. Medicineis now a little closer to that goal because of the work of twoimmunologists to delineate how T-cells recognize foreign or abnormalcells, and to identify the genes that code for the antigen receptorson T-cells.

For their pioneering efforts in basic science, Mark M. Davis,phd, Investigator at The Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Professorof Microbiology and Immunology at Stanford University School ofMedicine, and Tak W. Mak, phd, Department of Molecular Biologyat The Ontario Cancer Institute, Director, Amen Institute, andProfessor of Medical Biophysics at University of Toronto, werejointly honored with the 1996 Alfred P. Sloan Prize, awarded bythe General Motors Cancer Research Foundation.

Untangling the Intricacies of T-Cells

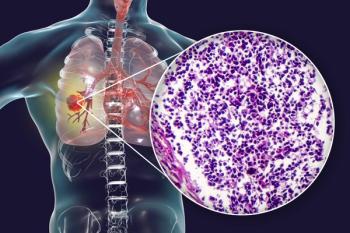

T-cells are a major force in the immune system, whether that systemis fighting off the common cold or cancer. T-lymphocytes playdifferent roles in combating not only bacterial or viral invadersbut also abnormal cells that arise in the body. Helper T-cellsfirst recognize these foreign antigens and then signal B-lymphocytesto pro

can recognize foreign proteins on the surface of an abnormal (eg,virus-infected) cell and destroy it. The role of recognizing foreignproteins falls to foreign protein (antigen) receptors (T-cellreceptors) on the T-cell surface.

In the past decade, scientists have been learning more about theseantigens and the T-cell receptors that respond to them. Findingthe genes that code for these receptors was regarded as the "HolyGrail" of immunology, because knowledge of T-cell receptorgene function is the key to understanding immune reactions andis essential to developing strategies to prevent and treat infectiousand autoimmune diseases, as well as cancers.

While a staff fellow at the National Institutes of Health in 1984,Dr. Mark Davis, together with Dr. Stephen Hedrick and others,reported the cloning of a gene that encodes the amino acid sequencethat controls a T-cell receptor in mice. Later at Stanford University,Dr. Davis and Dr. Yueh-Hsiu Chien found two other types of T-cellreceptor genes found to govern the two major types of T-cell receptors:the alpha-beta receptor and the gamma-delta receptor.

The alpha-beta receptor is the principal receptor occurring onmost T-cells in the body. It was found to recognize not only antigensbut also a molecule called the major histocompatibility complex(MHC) formed when proteins are degraded as part of normal cellmetabolism. The MHC gathers up bits of proteins (called peptides)left behind and displays them on its surface. These peptides includetumor cell-specific peptides.

The Mystery of T-Cells

"Before this, T-cell receptors were a very mysterious partof the immune system. We knew that B-cells recognized foreignentities using antibodies, but we didn't know what T-cells usedand how they 'see' both antigen and MHC together," Dr. Davisexplains.

Dr. Davis and colleagues have since directed their efforts tounderstanding how T-cells interact with antigen/MHC protein complexes,which turn out to be involved in almost every human immune response,including the recognition of tumor cells by receptors on killerT-cells. "One of the most exciting areas of cancer researchtoday involves boosting the T-cell response to tumor-related peptidesbound to MHC molecules," he adds.

Working independently, Dr. Tak W. Mak and colleagues at the OntarioCancer Institute and the University of Toronto identified genesfor the antigen receptor of human T-cells in 1984, ending a longquest in the immunology community. Dr. Mak's laboratory also detailedthe structure and function of T-cell receptors, including thechromosomal locations of the receptor genes, as well as the organizationof the gene's segments and their functions.

Using this new-found knowledge, Dr. Mak studied receptor genesin patients with T-cell malignancies, such as leukemia and lymphoma.This approach is now an established method that aids in the diagnosisof these cancers. One of the team's important discoveries wasthat chromosomal translocations (wherein a piece of one chromosomebreaks off and somehow attaches itself to another chromosome)can activate cancer-causing oncogenes. Extensive studies haveresulted in the identification of many chromosomal breakpointsand their links to malignancies.

"Designer Genes" and "Knock-Out" Mice

Starting in 1990, Dr. Mak's team developed transgenic mice bredto carry "designer genes" for specific T-cell receptors.Even more useful were the "knock-out" mice, bred tocarry mutations that "knocked out," or deleted, a specificimmune gene or function. These mice provide models to study genedeletions (which may be inherited or occur during one's lifetime)and immune dysfunction. By studying these mice, Dr. Mak has alsogained key insights into the poorly understood process of thymicselection of T-cells, ie, how T-cells "learn" to recognizeforeign proteins without destroying "self" proteins.New information on molecules required to assist T-cells in theiraction, the costimulatory proteins, has also come to light. Theseresults have important ramifications in treating recurrent infections,cancer, autoimmune diseases, and even AIDS.

"Any attempt to create T-cell-mediated immunotherapy forcancer rests on the foundation of Dr. Davis' and Dr. Mak's discoveries,"stressed Joseph G. Fortner, md, President of the General MotorsCancer Research Foundation in announcing the joint award. "TheT-lymphocyte is centrally involved in our resistance to some cancers.Dr. Davis' and Dr. Mak's work not only clarified the role of theT-cell receptor in immune reactions to cancer, but also the waysin which various substances may affect how the cell behaves. Thisunderstanding is very important to the development of vaccinesagainst cancer."

An example is the recently developed vaccine against melanoma,which involves deactivating tumor cells so that they are no longermalignant and then using them to stimulate an immune responsein the body. The tumor-destroying killer T-cells are primed torecognize the foreign proteins of the melanoma and attack activemalignant melanoma cells. Without the knowledge of how T-cellreceptors recognize their targets and how to trigger that response,creating this and future vaccines would have been impossible.

Dr. Davis received his undergaduate degree at Johns Hopkins andearned a PhD in molecular biology from the California Instituteof Technology in 1981. He was a postdoctoral and staff fellowat the Laboratory of Immunology at the National Institutes ofHealth. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in1993.

Dr. Mak, a Canadian citizen, received his bs and ms degrees fromthe University of Wisconsin, Madison, and his phd in biochemistryfrom the University of Alberta, Edmonton. He joined the Universityof Toronto faculty in 1976. In 1994, he was elected fellow ofthe Royal Society of London.

Articles in this issue

over 29 years ago

Deadly Human Parasite Discoveredover 29 years ago

National Program of Cancer Registriesover 29 years ago

Gut Reaction: New Locale for Antibody ActivityNewsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.