Immunotherapy Failure in Pancreatic Cancer Reveals Potential Path Forward

Negative trial findings suggest immune checkpoint inhibitors may not be the best type of immunotherapy to treat pancreatic cancer.

Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, failed to elicit a sufficient response rate in patients with previously treated metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, found a

“The results of the study very clearly showed that even in combination, immune checkpoint inhibitors are likely not going to work in pancreatic cancer-period,” said Neeha Zaidi, MD, of the Skip Viragh Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research and Clinical Care, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, during an interview with Cancer Network. Zaidi co-authored a corresponding

The trial was an international, multicenter study that enrolled 65 patients with metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma who were previously treated with either fluorouracil-based or gemcitabine-based treatment in the first-line setting. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either single-agent durvalumab, an anti–programmed death-ligand 1 (anti–PD-L1), or durvalumab in combination with tremelimumab, an anticytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4).

The trial had a two-part design: a lead-in safety study (part A), followed by an expansion study (part B). The trial would advance to part B only if part A showed an objective response rate (ORR) above 10% for either treatment.

Neither agent reached the ORR threshold, so the trial did not advance to the part B expansion study. Specifically, single-agent durvalumab had an ORR of 0% (95% CI, 0.00–10.58) and durvalumab in combination had an ORR of 3.1% (95% CI, 0.08–16.22). Both treatments had a median progression-free survival of 1.5 months; the median overall survival was also similar between treatment groups: 3.6 months for single-agent durvalumab and 3.1 months for durvalumab in combination. At 3 months, the disease control rate was 6.1% for single-agent durvalumab and 9.4% for durvalumab in combination.

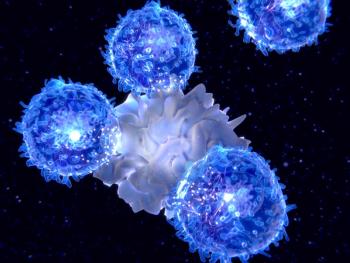

Although immune checkpoint inhibitor combination therapy has shown efficacy for immunogenic, “hot” tumors, such as melanoma and lung cancer, one key difference is that pancreatic cancer is not an immunogenic tumor, commonly known as a “cold” tumor.

“There are not a lot of immune cells within the pancreatic cancer,” said Zaidi, nothing that there are also immunosuppressive signals. “The question is how do we facilitate bringing in these immune cells?”

She said that combining immune checkpoint inhibitors may not be the answer. Instead, it may require a “multipronged approached,” one that involves different types of agents, such as vaccines or oncolytic viruses, that can prime the immune microenvironment so that the checkpoint inhibitors can then work.

Despite the negative findings, the trial did show that the durvalumab combination was “safely tolerated,” Zaidi added. For patients who received durvalumab combination therapy, 22% had grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events. By comparison, 6% of patients who received single-agent durvalumab had a grade 3 or higher event. The overall discontinuation rate due to treatment-related adverse events for both treatment groups was 6%.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.