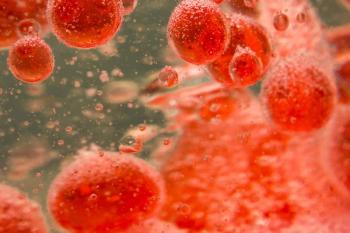

New Agents Add Options to Multiple Myeloma Management

As more and more new options come on the market, integrating them into proper management of multiple myeloma has become an important challenge.

A number of new therapies have been introduced for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM) over the last decade and a half. The success of some of those therapies has led to increased survival, and thus an increasing number of people living with the disease. As more and more new options come on the market, integrating them into proper management of MM has become an important challenge.

“There are more than 100,000 patients alive in the United States with MM,” said Carol Ann Huff, MD, of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, who spoke at the 11th Annual National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Hematologic Malignancies Congress, held September 30–October 1 in New York. The average survival has increased to 6 years with some of the newer drugs, she added; there have been 10 new therapies approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since 2004.

In 2015 alone, the FDA approved panobinostat, daratumumab, ixazomib, and elotuzumab for MM. Huff spoke about incorporating these agents into MM management, and how their mechanisms of action differ.

Panobinostat is a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, and was tested in the phase III PANORAMA 1 trial in combination with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and dexamethasone in relapsed/refractory MM. The trial included 768 patients, and treatment with panobinostat produced a 3.9-month progression-free survival improvement compared with placebo and bortezomib/dexamethasone.

There was no difference, however, with regard to response rates or overall survival, and the FDA initially did not approve the drug based on those results. A subgroup analysis, however, showed that patients who received at least two prior lines of therapy did respond, and on that basis the drug was approved.

Using the drug, however, is not simple. “There is not inconsequential toxicity,” Huff said. In the PANORAMA 1 trial, 25% of panobinostat patients had grade 3/4 diarrhea, compared with only 8% of placebo patients. Huff noted that there is ongoing work on combining panobinostat with other proteasome inhibitors that may help reduce that toxicity. “I suspect we will see some of those combinations,” she said.

One such drug is ixazomib, the first oral proteasome inhibitor, which allows administration of the first all-oral three-drug regimen for MM. The phase III TOURMALINE-MM1 trial tested ixazomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone vs the latter two drugs with placebo in 722 relapsed/refractory MM patients who had received 1 to 3 prior lines of therapy. The ixazomib patients had a median progression-free survival of 20.6 months, compared with 14.7 months without it (P = .012), and Huff said this benefit stretched across all prespecified subgroups including those deemed cytogenetic high-risk.

Again, the toxicity was higher with the study drug, with more patients experiencing rash and some gastrointestinal side effects. “Nevertheless, these side effects are manageable, and most patients do quite well,” Huff said.

The other recently approved rugs are monoclonal antibodies, including daratumumab and elotuzumab. The phase II SIRIUS trial showed that heavily pretreated patients achieved a 29.2% response rate with daratumumab, and a 1-year overall survival rate of 65%, which Huff said “is really impressive in this population.” Importantly, there was even a 21% response rate in patients who were refractory to several other medications including bortezomib and lenalidomide, providing a potential therapeutic option for patients who otherwise had none.

The toxicities to be aware of with this drug, she added, are infusion-related reactions. They occurred in 42% of patients in the SIRIUS study, and are predominantly seen on the first infusion of the drug. These often manifest as upper respiratory tract issues including nasal congestion, throat irritation, and cough. Huff said it is generally a well-tolerated antibody, though; premedication, usually with steroids, is required.

Combining daratumumab with bortezomib and dexamethasone also showed promise in a phase III study, the CASTOR trial. In that study, those receiving daratumumab had a 1-year progression-free survival rate of 60.7%, compared with only 26.9% without the antibody.

Another phase III trial, ELOQUENT-2, showed that elotuzumab, another monoclonal antibody, also can be effective. Combined with lenalidomide and dexamethasone, relapsed/refractory MM patients had a median progression-free survival of 19.4 months compared with 14.9 months with lenalidomide/dexamethasone alone (P = .0014). Notably, the median time to next treatment was 33 months with elotuzumab, compared with 21 months without it. With this drug, the infusion-related reactions occurred in only 10% of patients.

“These four agents have been incorporated into guidelines for previously treated patients,” Huff said. “Our treatment landscape has grown significantly, not just with these but with the ability to combine these with other agents.” She noted that a better understanding of treatment sequences and patient selection, especially in the relapsed/refractory setting, is still needed.

“I don’t think we have a cure, but we are hopefully converting this into a long-term, manageable disease,” Huff said.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.