- ONCOLOGY Vol 24 No 14

- Volume 24

- Issue 14

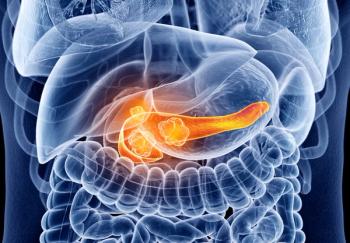

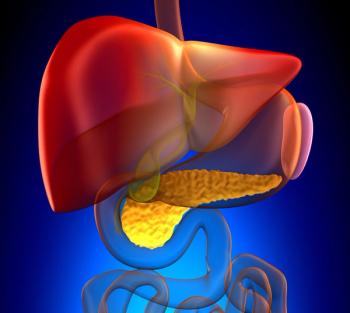

Recurrent Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma After Pancreatic Resection

The University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine faculty hold weekly second opinion conferences focusing on cancer cases that represent most major cancer sites. Patients seen for second opinions are evaluated by an oncologic specialist. Their history, pathology, and radiographs are reviewed during the multidisciplinary conference, and then specific recommendations are made. These cases are usually challenging, and these conferences provide an outstanding educational opportunity for staff, fellows, and residents in training.The second opinion conferences include actual cases from genitourinary, lung, melanoma, breast, neurosurgery, gastrointestinal, and medical oncology. On an occasional basis, ONCOLOGY will publish the more interesting case discussions and the resultant recommendations. We would appreciate your feedback; please contact us at second.opinion@uchsc.edu.

The patient is a 57-year old Caucasian female who presented with right upper quadrant pain and obstructive jaundice and was diagnosed with resectable pancreatic cancer. She underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) after preoperative biliary stenting. She subsequently presented to the clinic, where it was noticed that she had an elevated CA 19-9. CT C/A/P revealed multiple new liver lesions.

SECOND OPINION

Multidisciplinary Consultations on Challenging Cases

The University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine faculty hold weekly second opinion conferences focusing on cancer cases that represent most major cancer sites. Patients seen for second opinions are evaluated by an oncologic specialist. Their history, pathology, and radiographs are reviewed during the multidisciplinary conference, and then specific recommendations are made. These cases are usually challenging, and these conferences provide an outstanding educational opportunity for staff, fellows, and residents in training. The second opinion conferences include actual cases from genitourinary, lung, melanoma, breast, neurosurgery, gastrointestinal, and medical oncology. On an occasional basis, ONCOLOGY will publish the more interesting case discussions and the resultant recommendations. We would appreciate your feedback; please contact us at second.opinion@uchsc.edu.

E. David Crawford, MD

Thomas W. Flaig, MD

Guest Editors

University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine

University of Colorado Cancer Center, Aurora, Colorado

Case Presentation

DR. ARVIND DASARI: The patient initially presented to the ER at our hospital with right upper quadrant pain and obstructive jaundice. Radiographic evaluation showed a 2.7-cm mass in the head of the pancreas.

Subsequent work-up including EGD/EUS with FNA and CT scans revealed cT3N0M0 pancreatic head adenocarcinoma invading the duodenum. The patient also underwent dilatation of a malignant common bile duct stricture with placement of a plastic stent. Given that the patient did not have any evidence of metastatic or locally advanced unresectable disease, she underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) six weeks after initial diagnosis. Pathology revealed a 3.1-cm, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma invading the duodenum with extensive lymph node involvement consistent with pT3 N1 disease. She was seen in the oncology clinic four weeks after her resection for a discussion about adjuvant therapy.

The patient had no other medical problems and was working full time prior to her diagnosis. Her father died of an unknown lymphoma and her mother was a laryngeal cancer survivor. Complete physical exam was unremarkable except for her surgical scar, which was healing well. Lab work revealed normal blood counts, electrolyte panel, and renal function. Liver tests that were elevated at the time of presentation had also normalized. CA19-9 was 387 U/ml (normal range 0-35 U/ml) at time of initial diagnosis and 483 U/ml at the time of the clinic visit. Repeat staging scans were done a week after her initial clinic vist and showed new hypodense liver lesions.

Radiographic Evaluation/Pre-operative staging

DR. ARVIND DASARI: Dr. Russ, Could you describe the radiographic findings in this patient?

DR. PAUL RUSS: The initial CT scan of the abdomen with intravenous and oral contrast revealed a 2.7-cm, hypodense, hypovascular, solid mass in the head of the pancreas and also involving the uncinate process. In addition, there was dilatation of the pancreatic, intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts without any evidence of distant metastatic or lymph node involvement. However, the second CT scan done, at the time of her clinic visit, showed post-surgical changes with an ill-defined soft tissue mass in the operative bed. There were also five new hypodense lesions in the liver, with the largest lesion in the anterior segment measuring 1.3 × 1.5 cm. There were two lesions in the dome, measuring 1.1 cm and 8 mm, along with two additional subcentimeter lesions in the right lobe (Figures 1A-1D, 2).

DR. ARVIND DASARI: Are these findings typical of metastatic pancreatic cancer?

DR. PAUL RUSS: Because pancreatic adenocarcinoma is typically hypovascular compared to background pancreas and liver, the primary neoplasm is depicted as hypodense to the pancreas, and metastases as hypodense to the liver. However, some pancreatic adenocarcinomas remain occult, even with the use of advanced CT techniques, and in those cases the diagnosis can sometimes be surmised by using indirect, secondary signs like pancreatic and/or bile duct dilatation, and post-obstructive pancreatic atrophy. In this case, we see one of the typical hypodense lesions consistent with metastatic pancreatic cancer.

DR. ARVIND DASARI: What is the sensitivity and specificity of CT scans in staging pancreatic cancer?

DR. PAUL RUSS: CT scans can be > 90% sensitive for diagnosing primary pancreatic lesions greater than 2 cm, but their sensitivity is less for smaller lesions. [1] CT scans also have a high sensitivity (> 90%) and specificity (>80%) in demonstrating vascular invasion.[2] CT scans are also invaluable in staging and are sensitive in diagnosing macroscopic vascular invasion and liver metastases, but are not as useful in assessing lymph node and peritoneal metastases.[3] CT scans are also very sensitive in detecting liver metastases larger than 1 cm, but lesions smaller than 1 cm can be problematic since small, incidental, benign hepatic lesions are commonly depicted by CT.[4] Given the multiple lesions, the typical radiographic appearance of the liver lesions in the setting of an elevated CA19-9, these findings are most consistent with recurrent metastatic pancreatic cancer.

DR. ARVIND DASARI: There was significant discrepancy between the pre-operative clinical staging and the final pathological lymph node staging. Would the patient have benefited from additional staging work up?

DR. PAUL RUSS: MR and PET are two radiographic modalities that can be considered, but which are less commonly used in detecting and staging pancreatic cancer. A meta-analysis showed that the sensitivity of MR for diagnosing pancreatic adenocarcinoma was somewhat inferior to spiral CT (84% vs 91%), but that for determining resectability, the two modalities were equivalent.[5] It is reported that MR has an accuracy of 91% in correctly diagnosing sub-centimeter hepatic lesions as benign vs malignant.[6] Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has been shown to have a sensitivity and specificity of 85% and 96%, respectively, in differentiating an inflammatory pancreatic mass from a conventional pancreatic carcinoma.[7] Thus, MR and MRCP can be used as an adjunct to multidetector CT (MDCT) in selected cases.[4] Given its low spatial resolution, PET scan alone is not useful in locoregional staging, but it could have a role in diagnosing metastatic disease. However, fused PET/CT scan, which combines the functional and anatomical information of both modalities, shows promise in imaging patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma.[4]

DR. ARVIND DASARI: Dr. McCarter, what is the utility of laparoscopy in staging patients with pancreatic cancer?

DR. MARTIN McCARTER: Laparoscopy is a staging modality on which there is no clear consensus. Opinions range from recommending its use in all patients prior to laparotomy to recommending not performing it at all. Overall, I believe that staging laparoscopy is a useful tool to diagnose advanced disease not detected by imaging or EUS studies in a selected sub-group of patients at high risk of advanced disease including (a) large (> 3cm) primary tumors (b) tumors of the neck, body or tail of pancreas (c) high CA 19-9, weight loss, hypoalbuminemia (d) and in patients with equivocal findings of metastatic disease upon imaging.[8] Our patient clearly had resectable disease, per intra-operative staging and did not meet any of the criteria above. She would not have benefited from either additional scans or laparoscopy.

Surgical Management of Pancreatic Cancer

DR. ARVIND DASARI: The patient had pre-operative biliary stenting that was unfortunately complicated by stent blockage a couple of weeks later and required stent exchange. When is pre-operative biliary drainage indicated?

DR. MARTIN McCARTER: Biliary drainage can be performed surgically, percutaneously, or endoscopically with either plastic or metal stents. A recent well-designed multicenter, randomized trial compared pre-operative biliary drainage with plastic stents followed by surgery four to six weeks later (n = 106) with immediate surgery within a week of diagnosis (n = 96) in patients with cancer of the pancreatic head and elevated total bilirubin (2.3 – 14.6 mg/dl). In line with previous studies, this study failed to show any mortality benefit from pre-operative biliary drainage, and in fact showed that the group with pre-operative stenting had significantly higher morbidity within four months of randomization-mostly from cholangitis and stent occlusion.[9] However, this study used plastic stents and not self-expanding metal stents (SEMS), which have a longer patency and fewer stent-related problems than plastic stents because of their larger diameter.[10] Therefore, pre-operative biliary stenting is best reserved for patients with acute cholangitis and severe cholestatic symptoms, in whom surgery will be delayed because of neoadjuvant therapy or for other reasons. In such cases, the preferred approach is endoscopic.

DR. ARVIND DASARI: Could you review the surgical management of this patient and your selection of this approach?

DR. MARTIN McCARTER: The patient underwent a Whipple’s procedure; i.e., the classical pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) that’s done for tumors of the pancreatic head or uncinate process. It includes resection of the head of the pancreas; lower part of the body and pylorus of the stomach; proximal small intestine including the duodenum; the first 10-15 cm of the jejunum; and common bile duct (CBD), along with cholecystectomy. The jejunum is then anastamosed to the pancreas, bile duct and gastric stump.[11] Since its original description, there have been a number of modifications made to the Whipple’s procedure in an effort to improve outcomes and decrease morbidity. These improvements include preservation of the pylorus, total pancreatectomy, extended lymphadenectomy, and variations in pancreatic anastamoses. However, none of these variations have been shown to improve outcomes significantly. In contrast, resection and reconstruction of the portal vein (PV) or superior mesenteric-portal vein confluence (SMPV) can be performed with acceptable added morbidity and several retrospective studies have found that the median survival time remains similar (20-26 months) to those who undergo PD without SMPV resection.[12-16] On evaluation intra-operatively, our patient did not have any evidence of vascular invasion-however several peri-pancreatic lymph nodes were enlarged and were removed with the operation. Not surprisingly, one factor known to have a significantly favorable impact on outcome is the surgeon and hospital volume.[17-19] The NCCN guidelines recommend that pancreatic resections be done at hospitals that perform at least 15 – 20 resections per year.

Pathological Evaluation

DR. ARVIND DASARI: Dr. McManus, could you discuss the pathological findings here?

DR. MARTINE McMANUS: We received a PD specimen that included the distal stomach, duodenum, head of the pancreas, and multiple lymph nodes fixed in formalin (Figure 3). The tumor was in the head of the pancreas with a maximum dimension of 3.1 cm and with extension into the adjacent duodenum. Lymphovascular and perineural invasion were present. The common bile duct margin was positive and pancreatic neck surgical margin was close (0.3 mm). 12 out of 20 regional lymph nodes examined had metastatic tumor. Histological examination revealed poorly differentiated ductal adenocarcinoma with signet ring cell features invasive into the peripancreatic soft tissue.

DR. ARVIND DASARI: Could the positive margin explain the immediate recurrence after resection in our patient?

DR. MARTINE McMANUS: The majority of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas invade the peri-pancreatic adipose tissue and can involve the intrapancreatic bile duct as well as the duodenal wall. It is therefore very important to have standardized criteria for surgical staging. Approximately 90% of PD specimens have regional lymph node involvement. Only 15% have R0 resection, defined as a negative margin of at least 1 mm. About 43% have multiple positive margins, most commonly with involvement of the retroperitoneal margin (soft tissue that contains perineural tissue adjacent to the superior mesenteric artery).[20] Most recurrences arise in the pancreatic bed along this critical margin. Other than positive margins, pathologic factors associated with decreased survival duration include metastatic disease in regional lymph nodes, poorly differentiated histology, and increased size of primary tumor. Another important feature is the presence of pancreatic cancer stem cells, which compose just 1-5% of the tumor but are capable of unlimited self-renewal and are also resistant to chemotherapy and radiation, which makes them difficult to eradicate.[21] All of these factors probably played a role in the recurrence seen in our patient.

Medical Management

DR. ARVIND DASARI: Dr. Messersmith, our patient has unfortunately been diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Gemcitabine is the mainstay of treatment in this setting. Could you review the benefit of palliative gemcitabine chemotherapy?

DR. WELLS MESSERSMITH: The trial that established gemcitabine as the mainstay of treatment in this setting was conducted in 1997 by Burris and colleagues on 126 patients randomized to either gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2 bolus weekly × seven weeks followed by one week of rest then weekly × three weeks every four weeks thereafter) or 5-FU (600 mg/m2 weekly).[22] The primary endpoint was clinical benefit response, defined as a sustained improvement in cancer-related symptoms. Significantly higher clinical benefit response was seen in 23.8 % of gemcitabine-treated patients vs 4.8% of 5-FU-treated patients (P = .0022). Significant benefit with gemcitabine was also seen in the secondary end points, including median survival (5.6 months vs 4.4 months,

P = .0025) and one-year survival rate (18% vs 2%).

DR. ARVIND DASARI: Is there evidence that shows a benefit from adding another cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agent to gemcitabine in metastatic pancreatic cancer?

DR. WELLS MESSERSMITH: Several large phase III trials have been conducted combining gemcitabine with conventional cytotoxic agents such as exatecan, cisplatin, oxaliplatin, 5-FU, irinotecan, capecitabine, and pemetrexed but the primary end point of improved overall survival (OS) was not met in any of these trials. Some trials did show improvement in response rate or progression-free survival (PFS).[23] However, some investigators believe that combination therapy with a platinum or capecitabine may improve outcomes in patients with good performance status. Combination therapy with capecitabine or a platinum compound has been evaluated in several phase II and two phase III trials and, overall, failed to show a convincing improvement in outcomes. However, meta-analyses of these trials have consistently shown a slight survival benefit in favor of combination therapy. These benefits were even more marked in patients with excellent PS.[24]

These results are supported by a meta-analysis of 15 trials with over 4,000 patients comparing gemcitabine to gemcitabine combination therapy. [25] This study showed a modest OS benefit (hazard ratio, HR of 0.91, 95% CI, 0.85 – 0.97, P = .004) that was limited to trials with platinum or fluoropyrimidine-based regimens with no benefit from other combinations. However, within this study, a meta-analysis of five trials with 1,682 patients with information on baseline PS showed a more substantial survival benefit with combination therapy (HR = 0.76; 95% CI: 0.67 – 0.87, P < .0001) in patients with a good performance status (ECOG PS 0-1) in contrast to patients with a poor performance status (ECOG 2) who did not appear to benefit from combination therapy (HR = 1.08,

P = 0.40). Thus, these meta-analyses suggest that gemcitabine-based cytotoxic combination chemotherapy is beneficial in patients with good PS. However, most individual phase III trials are negative – suggesting that any absolute benefit is modest. Moreover, in a setting where the median survival is only six months, and the primary objective is symptomatic relief, the slight survival benefit may be outweighed by increased toxicity and complications with combination therapy. I would consider combination therapy in patients with excellent PS (ECOG 0-1) after a detailed discussion with them.

DR. ARVIND DASARI: How about combining gemcitabine with a targeted agent?

DR. WELLS MESSERSMITH: Overall, the evidence collected over the last decade has shown that adding cytotoxic chemotherapy to gemcitabine will probably not provide any meaningful benefit in OS. As a result, multiple attempts were made to improve outcomes by adding targeted agents to gemcitabine, including several in large phase III trials. Of these, the only agent shown to have any benefit was erlotinib, in a phase III study of 569 patients conducted by the National Cancer Institute of Canada in 2007.[26] Patients were randomized to gemcitabine monotherapy (administered as in the Burris trial) or in combination with erlotinib (100 mg po daily). Median survival (6.2 months vs 5.9 months, P = .038), 1-year survival (32% vs 17%) and PFS (HR 0.77, 95% CI, 0.64 – 0.92, P = .004) were significantly better in the combination arm. There is considerable doubt as to whether such a marginal benefit is clinically significant.

Current NCCN guidelines recommend single agent gemcitabine or, in patients with good PS, combination of gemcitabine with cisplatin, erlotinib or a fluropyrimidine. These guidelines also recommend fixed dose rate gemcitabine as a category 2B recommendation-however, based on the phase III trial that was published since, I do not believe that there is any benefit with this approach.

DR. ARVIND DASARI: If our patient progresses on first-line gemcitabine, what options are available for second-line therapy?

DR. WELLS MESSERSMITH: In contrast to the first-line setting, there are no recommendations for the second-line therapy of advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. However, current data suggests that a fluoropyrimidine in combination with oxaliplatin may have some activity. The phase II CONKO-003 trial randomized patients with gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer to 5-FU (2 gm/m2 over 24 hours) and leucovorin (200 mg/m2 over 30 minutes) on days 1,8,15 and 22 with (OFF) or without oxaliplatin (85 mg/m2 days 8 and 22) over a 42 day cycle. In a preliminary report, OFF was associated with longer OS (26 vs 13 weeks, P = .014) and PFS (13 vs 9 weeks, P= .012).[27] In another phase II study, oxaliplatin (130 mg/m2 on day 1) was evaluated in combination with capecitabine (1000 mg/m2 twice daily for 14 days). The doses of oxaliplatin and capecitabine were reduced in patients with age > 65 years or ECOG PS 2 (to 110mg/m2 and 750 mg/m2 respectively). Of the 39 evaluable patients, 1 patient had a partial response and 10 had stable disease. Median OS was 23 weeks (95% CI 17 – 31 weeks) and PFS was 9.9 weeks (95% CI 9.6 – 14.5 weeks). The 6-month and 1-year survivals were 44% (95% CI, 31%-62%) and 21% (95% CI, 11%-38%), respectively.[28] Based on these small studies, although it would be difficult to make definitive recommendations, a regimen containing oxaliplatin and a fluoropyrimidine (typically capecitabine for convenience) is a reasonable second-line choice in patients with good performance status. Insurance coverage, particularly in Medicare patients, can be an issue since oxaliplatin is not listed on all compendia for pancreatic cancer.

To summarize, this is a patient who presented with pancreatic cancer and who was found to have more extensive disease than was initially determined per peri-operative staging. She underwent pre-operative biliary stenting followed by an uncomplicated PD and presented to the clinic for discussion regarding adjuvant therapy, but was found to have new metastatic disease. She subsequently started palliative chemotherapy with single agent gemcitabine which she tolerated well, and had stable disease for three months before developing progressive disease. At that time, after discussion regarding second-line therapy with cytotoxic therapy vs enrollment in a clinical trial, she was started on a phase I clinical trial, per her wishes. She progressed rapidly on this trial and finally elected palliative care.

Concluding Remarks

DR. ARVIND DASARI: During evaluation of pancreas cancer, it is important to remember that CT scans have high sensitivity and specificity in primary tumor diagnosis and adjacent vessel invasion. They also have high sensitivity and specificity in detecting metastatic lesions greater than 1 cm. MRIs can be useful to evaluate subcentimeter metastatic lesions in the liver. CT scans also have limited utility in detecting lymph node and peritoneal spread. In cases where there is a high probability of occult metastatic disease, diagnostic laparoscopy is a reasonable approach.

In spite of modern treatment modalities, resectable pancreatic cancer continues to have a high rate of recurrence and mortality. These recurrences are secondary to multiple factors including high rates of positive surgical margins, lymph node involvement and tumor biology. In the metastatic setting, gemcitabine continues to be the mainstay of first-line treatment. Multiple attempts have been made to improve outcomes by adding a second cytotoxic or targeted agent, however, the only agents shown to have significant benefit are capecitabine and erlotinib, and even then, the benefits are slight and at the cost of side effects. Therefore, these agents should be reserved for patients with good performance status. In the second-line setting, a combination of oxaliplatin and a fluoropyrimdine is a reasonable option for patients with preserved performance status.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no significant financial interest or other relationship with the manufacturers of any products or providers of any service mentioned in this article.

References:

References

1. Bronstein YL, Loyer EM, Kaur H, et al. Detection of small pancreatic tumors with multiphasic helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:619-23.

2. Karmazanovsky G, Fedorov V, Kubyshkin V, et al. Pancreatic head cancer: accuracy of CT in determination of resectability. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:488-500.

3. Lu DS, Reber HA, Krasny RM, et al. Local staging of pancreatic cancer: criteria for unresectability of major vessels as revealed by pancreatic-phase, thin-section helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:1439-43.

4. Wong JC, Lu DS. Staging of pancreatic adenocarcinoma by imaging studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1301-8.

5. Bipat S, Phoa SS, van Delden OM, et al. Ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosis and determining resectability of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005;29:438-45.

6. Holalkere NS, Sahani DV, Blake MA, et al. Characterization of small liver lesions: Added role of MR after MDCT. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2006;30:591-6.

7. Ichikawa T, Sou H, Araki T, et al. Duct-penetrating sign at MRCP: usefulness for differentiating inflammatory pancreatic mass from pancreatic carcinomas. Radiology. 2001;221:107-16.

8. Callery MP, Chang KJ, Fishman EK, et al. Pretreatment assessment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1727-33.

9. van der Gaag NA, Rauws EA, van Eijck CH, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage for cancer of the head of the pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:129-37.

10. Moss AC, Morris E, Leyden J, et al. Malignant distal biliary obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of endoscopic and surgical bypass results. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:213-21.

11. Strasberg SM, Drebin JA, Soper NJ. Evolution and current status of the Whipple procedure: an update for gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:983-94.

12. Leach SD, Lee JE, Charnsangavej C, et al. Survival following pancreaticoduodenectomy with resection of the superior mesenteric-portal vein confluence for adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. Br J Surg. 1998;85:611-7.

13. Fuhrman GM, Leach SD, Staley CA, et al. Rationale for en bloc vein resection in the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma adherent to the superior mesenteric-portal vein confluence. Pancreatic Tumor Study Group. Ann Surg. 1996;223:154-62.

14. Tseng JF, Raut CP, Lee JE, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection: margin status and survival duration. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:935-49; discussion 49-50.

15. Raut CP, Tseng JF, Sun CC, et al. Impact of resection status on pattern of failure and survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;246:52-60.

16. Martin RC, 2nd, Scoggins CR, Egnatashvili V, et al. Arterial and venous resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: operative and long-term outcomes. Arch Surg. 2009;144:154-9.

17. Orr RK. Outcomes in pancreatic cancer surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:219-34.

18. Schmidt CM, Turrini O, Parikh P, et al. Effect of hospital volume, surgeon experience, and surgeon volume on patient outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a single-institution experience. Arch Surg. 2010;145:634-40.

19. Michalski CW, Weitz J, Buchler MW. Surgery insight: surgical management of pancreatic cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:526-35.

20. F B, I E, E H, P S. Pancreatic cancer - Pathology. Chinese-German Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;6:95-101.

21. Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1605-17.

22. Burris HA, 3rd, Moore MJ, Andersen J, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403-13.

23. Stathis A, Moore MJ. Advanced pancreatic carcinoma: current treatment and future challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:163-72.

24. Heinemann V, Labianca R, Hinke A, Louvet C. Increased survival using platinum analog combined with gemcitabine as compared to single-agent gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer: pooled analysis of two randomized trials, the GERCOR/GISCAD intergroup study and a German multicenter study. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1652-9.

25. Heinemann V, Boeck S, Hinke A, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized trials: evaluation of benefit from gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapy applied in advanced pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:82.

26. Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1960-6.

27. Pelzer U, Kubica K, Stieler J, et al. A randomized trial in patients with gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer. Final results of the CONKO 003 study. ASCO: J Clin Oncol; 2008. p. 215s.

28. Xiong HQ, Varadhachary GR, Blais JC, et al. Phase 2 trial of oxaliplatin plus capecitabine (XELOX) as second-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:2046-52.

Articles in this issue

about 15 years ago

Is This a True Renaissance for the Treatment of Prostate Cancer?about 15 years ago

Castration-Refractory Prostate Cancer: New Therapies, New Questionsabout 15 years ago

A Renaissance in the Medical Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancerabout 15 years ago

CTLA-4–Blocking Immunotherapy With Ipilimumab for Advanced Melanomaabout 15 years ago

Improving the Therapeutic Benefits of Ipilimumababout 15 years ago

Ipilimumab: A Promising Immunotherapy for Melanomaabout 15 years ago

Myth Busting: Does Real-World Experience Lead to Better Drug Choices?about 15 years ago

Lycium (Lycium barbarum)about 15 years ago

Pancreatic Adeno-carcinoma: New Approaches to a Challenging Malignancyabout 15 years ago

The War on Pancreatic Cancer: Are We Gaining Ground?Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.