Significant Barriers to Clinical Implementation of Tumor Profiling

While determining the genetic makeup of a patient’s tumor is a critical tool for precision cancer medicine, there are still several challenges and unanswered questions about large-scale clinical application of the methods.

The clinical implementations of tumor profiling may be even greater than previously recognized. However, large-scale cancer gene profiling while feasible still faces significant barriers. Researchers leading the largest genomic tumor profiling effort of its kind say such studies are technically feasible in a broad population of adult and pediatric patients with many different types of cancer.

While determining the genetic makeup of a patient’s tumor is a critical tool for precision cancer medicine, there are still several challenges and unanswered questions about large-scale clinical application of the methods. Just over half of patients in the study who gave consent and had tumor profiling ordered by a physician actually received results, due to a variety of technical and logistical factors.

In approximately 10% of cases, the test information was used in caring for the patient. Reasons for the attrition rate included absence of effective drugs, timing of genomic testing in the course of a patient’s disease, less than optimal access to targeted drugs or clinical trials, and patient and provider preferences.

Identifying these barriers allows researchers to develop and implement new solutions, with the goal of improving the rate of use of the genomic results. Overall, the turnaround time from receiving the sample to issuing a report of the findings was 5.3 weeks, a timespan the researchers said they have since shortened to less than 3 weeks.

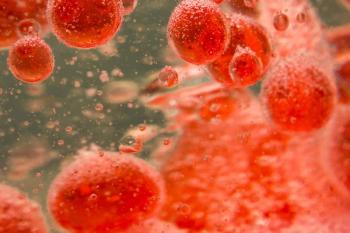

Profile tumor genotyping, which started in 2011, uses a platform called OncoPanel that comprehensively sequences hundreds of known cancer-related genes. The study wasn’t designed to measure whether tumor profiling made a difference in how patients fared, but it does lay the groundwork for more systematic study of the impact of genomics on clinical practice and patient outcomes.

According to the report, at least one actionable mutation or informative alteration was discovered in 73% of patients. Tumor profiling can also reveal rare mutations and other changes that make some cancers unusually responsive to targeted drugs. The report gave some examples of how genomic testing clarified or changed a patient’s diagnosis, which in turn altered treatment and prognosis.

A patient with blood cancer who had received several diagnoses was found through testing to have an unusual form of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), which predicted responsiveness to imatinib. The patient was treated with this agent and experienced a dramatic and sustained clinical response. A patient’s undifferentiated small bowel sarcoma was found to contain a KIT gene deletion, resulting in a revised diagnosis of GIST (gastrointestinal stromal tumor) that was successfully treated with imatinib.

While genomic results can be beneficial in guiding more personalized treatment for cancer patients, barriers still do exist when it comes to testing.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.