- Oncology Vol 29 No 1

- Volume 29

- Issue 1

Treatment Without Consent?

A delirious head and neck cancer patient does not have the capacity to make treatment decisions. Can we begin palliative radiation therapy without his consent?

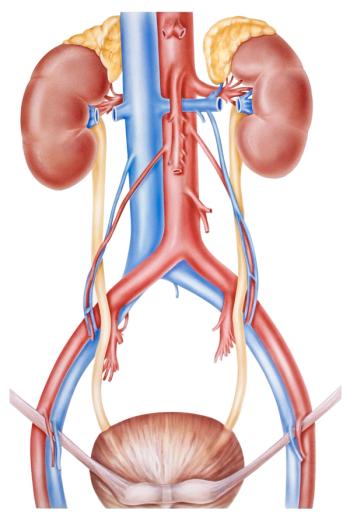

I received in transfer a man in his 50s with advanced base of the tongue cancer. He has a long history of complex mental illness and lives in a very difficult set of social circumstances. His head and neck cancer has clearly been neglected, because at this time it is occupying a large part of the floor of his mouth and pushing his tongue outside of his lips. He has extensive locoregional invasion and a great deal of pain, and was found on admission to have distant metastases in the lungs. He has a feeding tube, which was inserted at another hospital, and he recently underwent tracheostomy because of airway compromise. Probably because of his acute illness, opiate pain medicines, and his pre-existing mental illness, he is delirious, and I do not think that he has the decision-making capacity needed to make treatment decisions. I obtained a psychiatry consultation, and the psychiatrist agreed that he lacks decision-making capacity for complex decisions. He has no identifiable family or other surrogates, and there is no one who has power of attorney for healthcare decisions. I have asked the hospital attorney to begin the process of obtaining a guardian ad litem from the court, but she informed me that this process would take a week or more to complete. In the meantime, can we begin palliative radiation therapy for symptom relief without his consent?

Dr. Helft Responds

The main ethical issue at stake in this tragic story is surrogate decision making, which is an incredibly common clinical issue. A recent study by one of my own colleagues found that, among hospitalized patients over 65, almost half required a major surrogate decision during their index hospitalization. In very rough outline, one can think of three levels of surrogate decision making for incapacitated patients such as your patient. The first is when we use the patient’s own advance wishes, such as wishes spelled out in a living will or advance directive document. This level has the advantage of using information obtained directly from the patient. The second is often referred to as substituted judgment, and is by far the most common situation. Such situations occur when a patient lacks decision-making capacity for a given decision and we turn to legally authorized surrogates to put themselves in the patient’s place and make the decision. This might be a person who has been legally designated to have durable power of attorney for healthcare decisions, or more commonly, it might be a family member with legal standing to make decisions, such as a spouse or first-degree relative. Statutes vary from state to state, however, with regard to who is designated as a legal surrogate, so you will need to consult your hospital attorney to guide you in such situations. The last level of surrogate decision making is usually called the “best interest” approach, and is based on the idea that, when no one else is available, the deciding clinician must keep the best interests of the patient in central focus.

Your patient’s situation requires this last approach, I think, since radiation therapy is likely to provide some palliative benefit, and the longer you wait to begin it, the longer the patient’s suffering will continue. Such a “best interest” approach necessitates careful consideration of the risk-benefit ratio of the treatment in question. In this context, relatively innocuous treatments (eg, opiate pain management) require a different level of consideration than more invasive or dangerous interventions (eg, surgery). Radiation therapy probably falls somewhere in the middle of this spectrum. I think that, in the context you describe, out of consideration for the patient’s best interest, the most beneficent approach would entail radiation therapy as part of a comprehensive approach to this patient’s palliative care. So I believe it is ethical to begin radiation therapy without the patient’s explicit consent. However, I applaud the decision to obtain a court-appointed guardian who will be able to help with future decisions.

Disclaimer:The advice offered in this ethical consultation feature is based solely on the information supplied by readers, and is offered without benefit of a detailed patient history or physical or laboratory findings. The information is offered as a discussion of ethical issues and is not intended to be medical or legal advice and, therefore, should not be considered complete or used in place of a formal ethics consultation or in place of seeking advice from your ethics committee, legal counsel, or other available resources. One should never disregard or change medical advice or delay in providing it because of something that is printed here. The opinions expressed here are only those of the author and do not reflect the viewpoint of ONCOLOGY.

This case was originally published online August 18, 2014.

Articles in this issue

about 11 years ago

Chemotherapy for Soft-Tissue Sarcomasabout 11 years ago

Chemotherapy in Soft-Tissue Sarcoma: Where Do We Go From Here?about 11 years ago

Bisphosphonates in Breast Cancer: A Triple Winner?about 11 years ago

Bisphosphonates: Game Changers?about 11 years ago

Big Data: Not Really the Same as Level 1 DataNewsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.