Urologists More Likely to Treat Low-Risk Prostate Cancer

How low-risk prostate cancer is managed depends more on the diagnosing physician than the patient’s disease state. Men who were diagnosed by a urologist were more likely to receive a treatment performed by the urologist and more likely to receive a therapy rather than monitoring.

How low-risk prostate cancer is managed depends more on the diagnosing physician than the patient’s disease state, according to a study

Of the 12,068 patient cases analyzed, 19.9% of the patients were observed and 80.1% received active treatment. The rates of active surveillance varied widely, from 4.5% to 64.2%, among the 2,145 treating urologists included in the analysis. The rates of observation also varied according to the consulting radiation oncologist, ranging from 2.2% to 46.8% of patients.

The potential for morbidity but no effect on outcomes, particularly overall survival, is a concern when treating low-risk disease. “Public reporting of physicians’ cancer management profiles would enable informed selection of physicians to diagnose and manage prostate cancer,” concluded Karen E. Hoffman, MD, MPH, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and colleagues.

The authors analyzed a retrospective cohort of men, 66 years and older, who were diagnosed with low-risk prostate cancer between 2006 and 2009. The patients’ disease characteristics were retrieved from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registries, and the diagnosing urologists and consulting radiation oncologists were determined from Medicare claims linked to patient records.

A diagnosing urologist accounted for 16.1% of the variation in type of upfront treatment compared with observation, while tumor and patient medical characteristics accounted for 7.9% of the variation in management- more than double the impact came from the diagnosing physician rather than from a patient’s disease and other medical characteristics.

Adjusting for both tumor and patient characteristics, urologists who treat non–low-risk prostate cancer and urologists who were older were less likely to opt for observation in managing men with low-risk disease (P = .01 and P = .004, respectively).

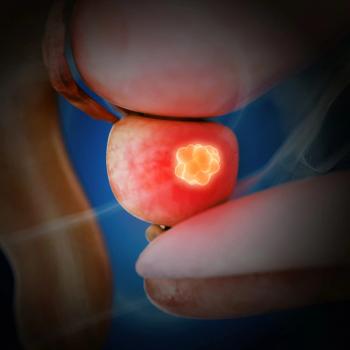

Types of upfront treatments chosen by the managing urologists included prostatectomy (P < .001), cryotherapy (P < .001), brachytherapy (P < .001), and external beam radiotherapy (P = .005), if the urologist performed these types of treatments in his or her clinic.

Men who were treated only by a urologist were more likely to undergo observation compared with men seen by a radiation oncologist and a urologist (43.8% vs 8.6%; P < .001). In total, 70.8% of men who went through observation saw only a urologist for management of their prostate cancer.

Low-risk prostate cancer is defined as a category T1-T2a clinical tumor, a Gleason score of 6 or lower, and a serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of less than 10 ng/mL; it is unlikely to affect survival or result in symptoms for patients. Since the advent of PSA testing, many more men are diagnosed with low-grade prostate cancer. Currently, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends against PSA screening due to the potential harm of biopsies, as well as morbidities as a result of unnecessary treatments.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical guidelines on prostate cancer recommend observation as an option for men with low-risk disease, since randomized clinical trials have shown that observation results in fewer side effects and morbidities, as well as similar survival outcomes to treatment.

“We postulate that the diagnosing urologist plays an important role in treatment selection because he or she is the first to convey the diagnosis to the patient and discuss disease severity and management options,” stated the authors.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.