Advances in the Treatment of Myelofibrosis

John Mascarenhas, MD, hosts a panel of experts who discusses current strategies used to stratify risk patients with myelofibrosis and their preferences for sequencing therapy.

At an Around the Practice presentation hosted by CancerNetwork®, experts discussed recent advancements in the treatment of patients with myelofibrosis. The panel was led by John Mascarenhas, MD, professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine, director of the Center of Excellence for Blood Cancers and Myeloid Disorders, and a member of the Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai in New York.

The expert panel also included Aaron Gerds, MD, MS, a physician at the Cleveland Clinic as well as assistant professor in the School of Medicine and member of the Developmental Therapeutics Program of Case Comprehensive Cancer Center at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio; Raajit Rampal, MD, PhD, a hematologic oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York; and Srdan Verstovsek, MD, PhD, director of the Hanns A. Pielenz Clinical Research Center for Myeloproliferative Neoplasms, chief of the Section for Myeloproliferative Neoplasms, and professor in the Department of Leukemia, Division of Cancer Medicine, at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Understanding Myelofibrosis

Mascarenhas: Can you explain what myelofibrosis is? How do you distinguish between primary and secondary disease?

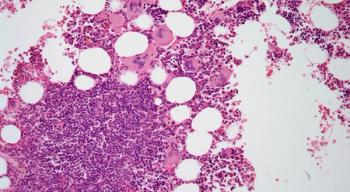

Gerd: The hallmark [of myelofibrosis] is scar tissue in the bone marrow, which is the common pathologic finding that we see. Mutations that occur in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway lead to this proliferation and growth and the ultimate scarring of tissue in the marrow. Over time, that scar tissue can lead to dysfunction in the hematopoietic process, and you see low blood counts in patients. As for primary vs secondary myelofibrosis, those words are tricky [because] primary myelofibrosis refers to [the] disease of bone marrow cancer. Secondary can mean either inflammatory scar tissue in the bone marrow vs a rheumatological disorder, for example, and it can also indicate myelofibrosis that has evolved out of a preexisting polycythemia vera (PV) or essential thrombocythemia (ET).

Mascarenhas: What are some examples of non–myeloproliferative neoplasm [MPN] secondary myelofibrosis? In what other settings could you see a myelofibrotic marrow?

Rampal: Fibrosis in the marrow is nonspecific, in many cases. Can you see it in other myeloid diseases? The answer is yes. Rarely, you see it in MDS [myelodysplastic syndrome]. A rare MDS subtype [exists], known as MDS with fibrosis, but beyond hematologic cancers, you can certainly see it in autoimmune conditions.

Mascarenhas: How do signaling pathway mutations and genetic and epigenetic alterations contribute to the pathophysiology of myelofibrosis?

Rampal: The hallmark of MPN pathogenesis [consists of] activations in the JAK-STAT pathway, which is a pathway that is involved in both inflammation and hematopoiesis. The disease is principally driven by unregulated JAK-STAT signaling. Other mutations can occur in the disease as well, and it’s very clear to us from both patient data and laboratory data that those mutations can alter the biology of the disease and, in many cases, advance it or cause it to be more aggressive. In addition, other pathways are activated by the JAK-STAT pathway, which we think plays a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. [Those mechanisms] are currently targets of inhibitors in clinical trials.

Mascarenhas: What are the biomarkers of interest?

Verstovsek: The prognostication in myelofibrosis has become complicated because we have identified multiple different biomarkers. Fifteen years ago, we started with the biomarkers that would be easy to understand, [such as] the number of white blood cells, blasts in the blood, or a clinical finding like symptoms or age. Since then, the other biomarkers we have identified [include] different driver mutations that activate the JAK-STAT pathway, like JAK2, CALR, or MPL mutations. [Patients who have] none of the 3 biomarkers are called triple negative, which we can test for by NGS [next-generation sequencing] panels in academic centers.

Mascarenhas: Are you doing tests like NGS in a serial fashion?

Verstovsek: We do repeat the testing automatically when clinical progression [occurs]. Ideally, [you would] test patients periodically, even when they’re stable, to predict a progression by acquisition of certain molecular abnormalities or cytogenetic abnormalities, but that is not a standard practice [because it’s] not feasible. This is [also] not being done because you can’t do much [with that information]. You do something when things change clinically, so the information [would be] applicable to or [would] influence the management. Then, it’s justifiable to test.

In a polling question, the audience indicated that fatigue was the most common symptom they saw in their patients with myelofibrosis (poll question 1).

Mascarenhas: What drives fatigue in myelofibrosis?

Rampal: Often, we need to figure it out. For example, if a patient has anemia, it’s [important to consider if it’s the] anemia driving the fatigue, or the disease, or both. Commonly, the answer is both, but it’s hard to tease out that answer. Aside from that, we have a lot of hypotheses about what drives fatigue. We blame cytokines, [for instance]. There may be truth to that because we do see a correlation between improvements in cytokine profiles in patients treated with JAK inhibitors and improvements in symptom burden. Fatigue improves despite patients developing some degree of anemia, so the answer is that [the reason behind fatigue] is often multifactorial.

Mascarenhas: How do you formulate your treatment plan based on symptoms?

Verstovsek: [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidance suggests using MPN 10 [MPN Symptom Assessment Form Total Symptom Score], a questionnaire that would cover the 10 most common symptoms. We use that questionnaire as a guide for discussion and it becomes a part of the medical record. If symptoms are affecting the patient’s quality of life [QOL], that is a trigger to [work with them] to improve QOL.

Mascarenhas: How are you generally classifying myelofibrosis?

Verstovsek: Many [classifications] are fixed on the grade of fibrosis in the bone marrow, [which] may have some significance on the outcome of the patients, but there are many other factors. Prognostication in terms of life expectancy does not depend solely on the degree of fibrosis. We look at patient, genetic, and chromosomal characteristics, as well as comorbidities, in deciding when to intervene. The factors would be assessment of QOL, to see whether we can control that, as well as bone marrow failure and anemia, to see whether the patient should be referred for bone marrow transplant.

Considerations for Treatment of Myelofibrosis

Mascarenhas: Can treatment be distinguished for primary and secondary myelofibrosis, or is it broad for all subtypes?

Verstovsek: Apart from the prognostication that we discussed, I do not apply risk of dying to decide whether I should treat the patient for anemia, for [symptoms in the] spleen, or for their QOL. The trigger is recognition of poor QOL. If the spleen is big and the patient is not in pain, I would ask a few more questions. Unless you ask questions and engage with the patients, you’re not going to recognize those problems. That applies to post-ET, post-PV, or primary myelofibrosis to the same degree, although [there are differences related to the] application of different therapies.

Mascarenhas: Where do clinical trials fit in terms of assessing patients for novel therapies?

Verstovsek: In a frontline setting, if platelets are above 50 109/L, you have 2 drugs: ruxolitinib [Jakafi] or fedratinib [Inrebic]. But neither is supposed to be given to patients with platelets below [that level], [which includes] about 10% to 15% of patients. [Patients with those low levels] typically have a low red blood cell count, and their spleen is not as big. This is a cytopenic patient in the frontline setting who needs something new. JAK inhibitors cover the spleen and symptoms, but they may worsen the anemia. In the frontline setting, anemia compromises the delivery of JAK inhibitors, so you need a drug for anemia. Drugs have been developed, like luspatercept [Rebozyl], to be combined with JAK inhibitors in the frontline setting. You want a combination that would enhance the JAK inhibitors, [and lead to] more spleen and symptoms control and other biological effects on the disease. Then, the durability of the response is much longer.

Treating a Patient With Primary Myelofibrosis

Patient Case 1

- A woman, aged 67 years, presented to her primary care physician with fatigue, increased bruising, and left upper quadrant abdominal pressure for the past 2 months.

- Medical history: well-controlled hypertensionAbdominal exam: palpable spleen about 4 cm below the costal margin Laboratory values:

- Hemoglobin: 9.8 g/dL

- Platelets: 215 109/L

- White blood cells: 17 109/L

Bone marrow biopsy showed hypercellularity, increase in atypical megakaryocytes, grade MF-3 fibrosis, and CD34/CD117+ staining in 1.3% blasts

30% JAK-V617F mutation

Diagnosis: primary myelofibrosis

In a polling question, most of the audience indicated that that they would treat this patient with ruxolitinib (poll question 2).

Mascarenhas: If you saw this patient, what would be your first-line therapy?

Verstovsek: I would not watch and wait. Age 67 [years] is still good for transplant. Further assessment with an NGS panel may push me to recommend the transplant even faster. We want to eventually cure the patient; that would be the goal. In between today and when the patient has the transplant, I treat for the symptoms and the spleen. If the anemia worsens through therapy with JAK inhibitors, you may add an anemia drug on top of it to help the patient get to their transplant in the best possible shape.

Gerds: What do you do to measure response?

Rampal: That’s a great question, and we’ve got to separate out what we do in clinical trials vs what we do practically speaking. It depends to some degree on what the treatment goals are. One of the treatment goals we would all agree with is to make the patient feel better, for which you can use the total symptom score. On the other hand, just talking to the patient and getting that assessment makes a difference. Let’s say the patient goes to stem cell transplant; making them functionally feel better makes a difference, but [so does] spleen size. On a high level, if we have a patient who is not a transplant candidate and their spleen shrinks enough that they feel comfortable and their symptoms are improved, that [can be considered] a response.

Gerds: What are some things you look for when you consider changing therapy?

Verstovsek: I talk to the patient to understand whether there is a benefit [of the current therapy], I palpate the spleen, and I look at their weight. Then my goal would be to maintain that benefit, even if it’s slowly going away, by adding another agent to the JAK inhibitor. Use of pacritinib is coming as an investigational agent for patients with low platelets. That would be my first choice if I had it today. I don’t have it yet, but hopefully [I will soon]. I would expand on that first line for as long as possible before I would change. In the second-line setting, we have agents that are being tested and we also have fedratinib, which is being used in the second-line setting as a JAK inhibitor. Momelotinib is [being examined in clinical trials as well], which [represents] a very interesting concept.

Rampal: One of the striking things with [momelotinib] is that [we saw] an anemia benefit, described by increases in hemoglobin and changes in the

proportion of patients getting transfused. Of course, we know with JAK inhibitors that anemia is a nontarget effect. With the mechanisms of action of momelotinib hitting other pathways, we think that is probably the mechanism by which it is contributing to an anemia response. This is a profile of a JAK inhibitor, and it’s not one-size-fit-all. For our cytopenic patients, we’ve been talking about pacritinib and the hopeful approval of that drug, which clearly has a benefit for patients with cytopenia. It doesn’t require dose modification based on platelet count, so that becomes an important tool in the arsenal. Then, coming to momelotinib, some patients may need something beyond just a drug for anemia. The patient who has symptomatic splenomegaly and who has anemia won’t benefit from single-agent daratumumab or other related drugs. But momelotinib [may lead to] spleen size reduction and potentially anemia benefit. We’re beginning to see niches for these different drugs that will greatly benefit the patients.

Verstovsek: What is the alternative pathway that the pacritinib affects in addition to the JAK pathway?

Mascarenhas: Pacritinib is interesting. There are differentiating factors [compared with] JAK inhibitors in late-stage testing. Pacritinib inhibits IRAK1, beyond JAK, and in doing so it likely affects a signaling pathway through the toll-like receptor, myosin complex, and then downstream to NF- B [nuclear factor light chain enhancer of activated B cells]. Hitting this alternative but relevant pathway in addition to JAK likely explains why this drug is less myelosuppressive [vs ruxolitinib/infigratinib]. You can give a full dose and enjoy symptom and spleen benefits with less myelosuppression. Some of the differences that we’ll see with these JAK inhibitors are likely due to their kinome profile and some of the other targets that they hit.

Patient Case 2

- A man, aged 75 years, presented with shortness of breath, drenching night sweats, and fatigue.

- Medical history: significant for high-risk primary myelofibrosis, diagnosed 1 year ago Baseline platelets: 81 109/L

- He was started on ruxolitinib and is currently on 10 mg twice daily.

- His platelet counts have dropped to 37 109/L and his hemoglobin is 8.2 g/dL.

In a polling question, most of the audience indicated that that they would treat this patient with pacritinib (poll question 3).

Rampal: I would not increase the dose of ruxolitinib. However, if someone is having a benefit, we must be careful. Of course, going by the FDA label, we need to attenuate, if not stop, ruxolitinib, [but] we cannot do that suddenly and risk withdrawal syndrome. In a practical sense, one could attenuate the dose of ruxolitinib and see if the platelets get better—Do they improve?—and then maybe rechallenge. That is not an unreasonable option. Another clear option would be to consider switching to pacritinib, which will hopefully be approved soon. In this scenario, we have a highly symptomatic patient. They need JAK inhibition and in this circumstance, pacritinib wouldn’t require dose modification due to the thrombocytopenia. It may be a fit for this patient.

Mascarenhas: From a safety standpoint, do these drugs have differences among their toxicity profiles?

Verstovsek: There are some, but they don’t affect the management too much. Fedratinib has some mild [gastrointestinal] toxicities such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea; you can prophylactically treat them easily with medications. Pacritinib could possibly be considered first in a patient who has platelets of 81 109/L because the intensity matters. There is no need for dose adjustments. This is the area where we expect new developments, [so we can understand] what the best approach is in the frontline setting [among] those 3 drugs for patients with low platelets. When the platelets go down to 37 109/L, it is certainly not easy to manage with the currently available medications, so we welcome the new development of pacritinib.

Reference

NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Myeloproliferative neoplasms, version 2.2021. Accessed February 10, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mpn.pdf

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.