Diagnosing Bladder Cancer: Best Practices in Workup and Staging

Shared insight on the standard work-up and staging practices used when a patient presents with newly diagnosed bladder cancer.

Episodes in this series

Transcript:

Petros Grivas, MD, PhD: Talking about the diagnostic work-up, which again, is mostly done by an urologist, Nerina, if you can give us your thoughts. When we see these patients in the clinic, what testing do we do, assuming the cystoscopy and maybe a TURBT [transurethral resection of bladder tumor] was done? What other tests do we do in terms of imaging, maybe biomarkers? [Do you have] any comments on that?

Nerina T. McDonald, PA-C: I think with biomarkers, the NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guideline recommends germline testing and genetic counselor referrals, especially if patients are presenting at a younger age, or have a family history of colon or endometrial malignancy. You’re assessing for Lynch syndrome, DNA mismatch repair deficiency mutations, and other hereditary conditions. In terms of imaging, if there is evidence of muscle-invasive disease, we would get complete staging, including a CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, to assess for other sites that could potentially be there.

Petros Grivas, MD, PhD: I totally agree, Nerina. I think that’s exactly the standard practice, imaging with a CT [of the] chest, abdomen, and pelvis, as you pointed out. And ideally, we use IV [intravenous] contrast for better-quality images. Sometimes, we have this challenge of patients having kidney failure, and IV contrast may be a challenge. Lisa, do you do an MRI in those cases with gadolinium, where you can use lower GFR [glomerular filtration rate] thresholds? How do you deal with that kidney impairment, or rarely, allergies to IV contrast?

Lisa Adams, PA-C: Often, if that is an issue, we will get a noncontrast CT [of the] chest, and then MRI imaging of the abdomen and pelvis to get a better sense of staging.

Petros Grivas, MD, PhD: Thank you. I think we do the same thing here. To add to this great discussion, we always think about, especially for metastatic disease, what else the patient may need. I totally agree, Nerina, germline testing is something we are learning about more and more because germline mutations are much more common than we thought. And we frequently send patients to genetic counseling, to your point, so I totally agree with that. A good family history assessment is key, and now we use nurse navigators more and more to try to ask the patients ahead of time about their broader family history and different degrees of relatives.

The other thing that comes to mind is genomic testing for tumor somatic mutations. We send tumor tissue to look for different genomic biomarkers. Traditionally PD-L1 has been something we looked at, but I think it’s not that useful anymore in urothelial cancer, mainly because we usually tend to start with chemotherapy in most patients. But we send genomic sequencing for all patients with metastatic disease because we look at different mutations, genomic alterations. We’ll talk a bit about erdafitinib in a second, and that’s for only select patients based on FGFR2 or FGFR3 mutations or fusions. It’s definitely an important message for the audience that if you have a patient with metastatic urothelial cancer, make sure to send at least tumor tissue for genomic testing. And in some cases, many of us may also send circulating tumor DNA to complement that and capture the heterogeneity of the disease. That’s a great discussion.

Emily, you are focusing on urinary cancer and have great experience. Can you tell us a bit more about the staging of bladder cancer? We do the multidisciplinary clinic together, and this comes up frequently. Can you drive us through, the diagnosis is [made with] usually cystoscopy, TURBT, sometimes urine cytology. Tell us a bit about the staging and the work-up of those people.

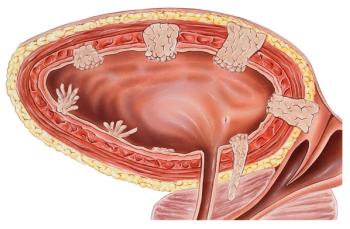

Emily S. Weg, MD: T [tumor] stage is usually something we want to get pathologically, so we’re looking for muscularis propria to be present in the specimen from the TURBT so that we can assess whether this is muscle-invasive disease or not. So typically, we want to establish that this is muscle invasive on the TURBT specimen. Then we always look at the scans with our radiologist and our bladder cancer multidisciplinary clinic to also have them weigh in on whether they think there’s some suspicion of extravesicle, or extension beyond the bladder, on the CT scan. Obviously, MRI is much more sensitive for detecting T3 or T4 disease, but sometimes we can even see it on a CT scan. Then the nodal status is something that obviously we would just see on a baseline-staging scan. It’s also always helpful to be able to discuss those scans in real time with the radiologist and point out all of the more or less suspicious nodes, and get an expert interpretation of the degree of suspicion for lymph node involvement.

We often end up, by the time we see patients, they also have had multiple scans over the last several months. Usually by the time they get sent to our multidisciplinary clinic, this has been worked up with maybe an initial scan at the time of presentation, and then the CT IVP [intravenous pyelogram], or a CT [of the] abdomen and pelvis with contrast once we realize what is going on, maybe after the cystoscopy before the TUR [transurethral resection]. So it’s always helpful to have multiple time points where you can look for growth or stability in any indeterminate lymph nodes.

Petros Grivas, MD, PhD: Thank you, Emily. Great points, absolutely. Speaking about all those factors and the need for a multidisciplinary approach, obviously, as you mentioned, tissue is the issue. You need to have tissue confirmation and also adequate staging. And this can be nuanced sometimes, to your point, sometimes muscularis propria may not be represented in the tissue sampling of a TURBT, the transurethral bladder tumor resection. If it is a T1, we always repeat the TURBT to ensure muscularis propria presence, and even if it is present, there’s the risk of understaging. I think it’s an important point that the urologists do that, repeat the TURBT to minimize the chance of understaging.

And the clinical staging, to your point, Emily, takes into account the pathology information from the TURBT, but also the exam under anesthesia and imaging. Because I know you and I have done this before, you may have a case that looks like a clinical T3 with extravesical extension, as you mentioned, and hydronephrosis, but in tissue, you cannot prove the muscularis propria invasion. But if everything looks like T3, we treat this patient as a T3 stage. Right?

Emily S. Weg, MD: Exactly.

Transcript edited for clarity.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.