Does Radioactive Iodine Post Reoperation Improve Thyroid Cancer Outcomes?

A study shows that receipt of radioactive iodine after reoperation may not be associated with improved outcomes.

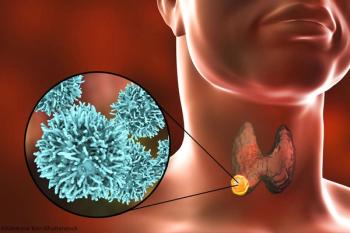

Adjuvant radioactive iodine (RAI) after reoperation for recurrent or persisting papillary thyroid cancer following initial treatment might not improve clinical outcomes, according to findings from a retrospective cohort analysis of data for 102 patients treated at a tertiary referral center.

Post-reoperation thyroglobulin levels were similar between patients who received RAI and those who did not, study authors

“Structural recurrence after reoperation occurred in 18 of 50 patients (36%) in the reoperation with RAI group and 10 of 52 patients (19%) in the reoperation without RAI group,” noted senior study author Michael W. Yeh, MD, of the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. The difference was not statistically significant in the team’s multivariate analysis.

“This study admirably addresses a very challenging question where there is little established data,” Allen S. Ho, MD, director of the head & neck cancer program and co-director of the thyroid cancer program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, told Cancer Network.

The study suggests that RAI after a reoperation should not be the default treatment, Ho noted. “Rather, it may be considered on a case-by-case basis, as already described in the 2015 American Thyroid Association Guidelines,” he said.

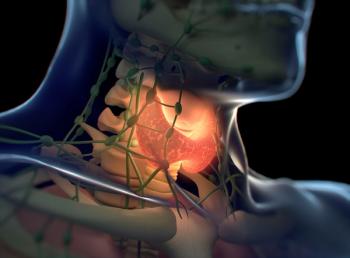

“The main established treatment for this population is surgery (reoperation). RAI, especially a second dose after reoperation, is considered an adjuvant treatment rather than the primary driver of outcomes in this scenario,” said Ho.

The patients who received RAI had more advanced disease, cautioned Ho and Robert Udelsman, MD, FACS, FACE, director of the Endocrine Neoplasia Institute at the Miami Cancer Institute, Baptist Health South Florida.

“They were not randomized, so you have to assume that there was a reason the doctors elected to give I-131 to one group and not the other. Generally speaking, most of us tend to offer more aggressive treatment to patients with more aggressive disease,” Udelsman told Cancer Network.

The study findings might indicate that RAI has no impact in this patient population, or that patients in the RAI group would have experienced worse outcomes had they not received RAI, according to Ho and Udelsman.

“Any retrospective study carries a fair amount of selection bias and while their multivariate analysis attempted to mitigate that, we can’t use a paper like this to change practice directly,” Andrew G. Shuman, MD, FACS, of the University of Michigan Medical School and Veterans Administration Ann Arbor Health System told Cancer Network.

The study “fits within a trend in thyroid cancer management, toward more consideration of treatment de-escalation and rethinking how aggressive we need to be with treatment in general,” Shuman said. “I think consideration of adjuvant RAI in the setting of regional recurrence is one that still needs to be driven by individual patient characteristics and risk factors.”

The authors did not address the role of diagnostic RAI scans in treating recurrent thyroid cancer.

In the past, many patients with thyroid cancer received RAI “either unnecessarily or in doses that were too high for the degree of their disease. Being overly aggressive is not necessarily a good thing,” said Udelsman.

This study raises an issue worth pursuing in a randomized prospective clinical trial, he noted.

“As the authors point out, the only real way to definitively answer this issue is with a randomized prospective trial in patients who undergo reoperation for papillary thyroid cancer and then would be randomized to either receive or not receive RAI therapy,” said Udelsman.

“The logistics involved in performing such a trial would be complex, involving multisite coordination and expense,” added Shuman. “While that would be ideal, I think that for the near future, the field is going to need to make clinical decisions without the best-quality data to drive them.”

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.