Fukushima Screening Program Sheds Light on Pediatric Thyroid Cancer

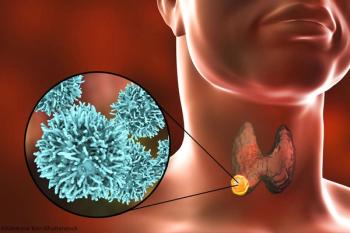

The thyroid screening program put in place after the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station accident resulted in the diagnosis of a number of pediatric thyroid cancers.

The large-scale mass ultrasound thyroid screening program put in place after the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station accident resulted in the diagnosis of a number of thyroid cancers, but there were no major changes in overall characteristics within 5 years of the accident, according to a study published in JAMA Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery.

“This study indicates that a large pool of thyroid cancers exist, which are not recognized as clinical caners without screening, from a relatively young age,” Akira Ohtsuru, MD, PhD, of Fukusima Medical University, and colleagues wrote.

After the 2011 Fukushima accident, the Japanese government put in place a health surveillance program, including thyroid screening that looked at residents aged 18 or younger at the time of the accident. The clinical characteristics of thyroid cancers screened during the first 5 years after the accident were analyzed.

The study included 324,301 children and young adults screened during two screening periods (2011–2013 and 2014–2015). During the first round, 116 malignant or suspected thyroid cancers were detected; during the second round, 71 were detected.

The most common type of thyroid cancer diagnosed was papillary thyroid cancer (98%). The distribution pattern of the incidence rate by age group at the time of screening increased with older age in both rounds of screening. For those aged 15 to 17, the incidence rate detected by screening was 29 cases per 100,000 person-years. That increased to 48 cases per 100,000 person-years for those aged 18 to 20, and again to 64 cases per 100,000 person-years for those aged 21 to 22.

“Although a longer observation period is needed, this pattern by age at the time of the accident differs from that of the Chernobyl nuclear power station accident; for example, there was a higher frequency of cases of cancer at younger ages with a relatively short latent period after the Chernobyl nuclear power station accident,” the researchers wrote. “Thus, an association between the large number of thyroid cancers detected and radiation exposure is thought to be very unlikely, in addition to the very low doses of radiation in the Fukushima nuclear power station accident.”

In an editorial published with the study, Andrew J. Bauer, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and Louise Davies, MD, MS, of Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, discussed the artificial inflation of cancer rates that can occur when a screening program is put in place for a cancer that was not previously screened.

“This artificial inflation is a problem, because it is then impossible to tell which changes were due to the natural disaster, and which were owing to detection of subclinical disease as a result of the screening program,” they wrote.

To avoid this in Fukushima, the screening program was put in place after the disaster but before the cancers would be expected to develop.

“The diagnosed children and adolescents had their cancers removed, eliminating information on natural progression, which, as Ohtsuru et al. suggested, would take 30 years or more to define based on a simulation model of cancer progression,” Bauer and Davies wrote. “As such, the Fukushima data provide no information to tell us which cases were overdiagnosis of disease that would have remained indolent, and which were early diagnosis of disease that would have ultimately progressed with regional and distant metastasis.”

These data “strongly suggest that population-based thyroid ultrasound screening for low-risk pediatric patients would not be advisable,” they concluded.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.