Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma: Surveillance or Immediate Biopsy, Surgery?

As part of our coverage of the 2016 American Thyroid Association Annual Meeting we discuss active surveillance vs immediate lobectomy or thyroidectomy in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma.

As part of Cancer Network’s coverage of the 86th Annual Meeting of the American Thyroid Association (ATA), held September 21-25 in Denver, we spoke with R. Michael Tuttle, MD, an endocrinologist and thyroid cancer expert at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Dr. Tuttle has served as a chair of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) thyroid cancer guidelines committee, and serves on the ATA guidelines committee.

- Interviewed by Bryant Furlow

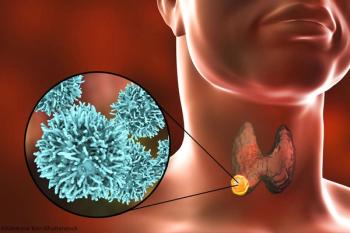

Cancer Network: Subclinical or indolent papillary thyroid microcarcinomas have become much more frequently detected over recent years. Why?

Dr. Tuttle: I think the primary reason for the dramatic increase in the diagnosis of papillary microcarcinomas is that incidental thyroid nodules are increasingly being described on imaging studies done for other reasons. For example, carotid ultrasounds commonly identified small thyroid nodules incidentally. Likewise, CT scans and MRI scans done for unrelated evaluations of the neck often identify the small nodules. Also, well-meaning primary care physicians occasionally order an ultrasound to evaluate the function of the thyroid when that evaluation is best done just with thyroid blood tests.

When you couple incidental findings with our improved ability to recognize nodules that are highly likely to be malignant based on the ultrasound characteristics, as well as our improved ability to biopsy smaller and smaller thyroid nodules, you have the perfect storm for increased detection and diagnosis of the large reservoir of previously subclinical thyroid cancers.

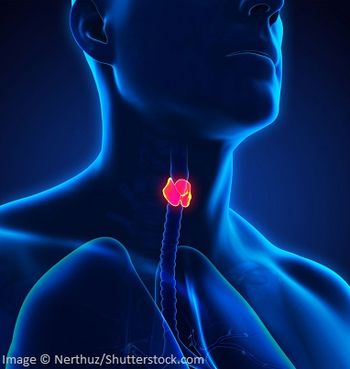

Cancer Network: What is the rationale for undertaking active surveillance rather than immediate thyroidectomy?

Dr. Tuttle: The primary rationale for considering active surveillance instead of immediate thyroidectomy is the lack of any prospective data demonstrating that immediate treatment of these very low-risk thyroid cancers has any demonstrable survival benefit. Furthermore, it is not even certain that one can decrease the risk of cervical lymph node recurrence if the primary tumor was resected with either lobectomy or total thyroidectomy. So in the absence of any proven benefit, one has to question whether or not therapy should be offered.

Secondly, there are many patients who are quite reluctant to have their thyroid removed. Sometimes it is because they are worried about the risk of thyroid surgery, even though these risks are small in experienced hands. But in other patients, they are concerned that they just won’t feel well if they have to go on thyroid hormone replacement therapy after thyroid surgery. Many of these patients have had a family member or friend have thyroid surgery and experienced difficulty with weight loss, fatigue, and an overall decline in quality of life.

Conversely, many patients want thyroid cancer removed from their body as soon as it is diagnosed because they can’t fathom living with thyroid cancer without therapy, no matter how small the tumor is and no matter how safe observation may be.

Therefore, I think it’s important that we provide patients with very low-risk thyroid cancer the option of either immediate surgery or an observational active-surveillance management approach, based on a clear shared decision-making process where the risk and benefits of each approach are carefully weighed and balanced with patients’ desires and expectations.

Cancer Network: What are the consequences of unnecessary thyroidectomy soon after diagnosis of papillary microcarcinomas?

Dr. Tuttle: In experienced hands, thyroid surgery is an exceptionally safe surgery, with almost no mortality and morbidity rates that would include permanent damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve in about 1% of patients and permanent hypoparathyroidism in fewer than 3% to 4% of patients. Unfortunately, in the United States, most thyroid surgeries are not done at higher-volume centers by very experienced surgeons. Therefore, the rate of complications is expected to be higher for the average patient being taken care of outside of major thyroid cancer centers.

Cancer Network: What does active surveillance for papillary microcarcinomas entail?

Dr. Tuttle: Our active surveillance approach entails thyroid ultrasound evaluations of the entire thyroid as well as the lymph nodes in the central and lateral neck approximately every 6 months for 2 years. Once stability has been documented for 2 years, we do the ultrasound yearly from years 3 through 5, and then less frequently after that depending on the size of the nodule, the location of the nodule, and the preference of the patient.

We obtain thyroid function test yearly to ensure the thyroid continues to function normally. We don’t generally plan additional biopsies or additional imaging unless we begin to see structural disease progression.

Indications for thyroid surgery include an increase in the size of the biopsy-proven primary tumor of more than 3 mm, evidence of invasion into or through the thyroid capsule, or newly identified abnormal lymph nodes in the neck. Obviously, the patient can change their mind at any point during observation and elect to move to surgical intervention even in the absence of structural disease progression.

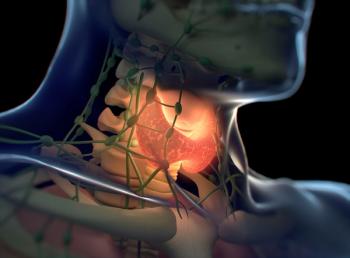

Cancer Network: Can you please describe the decision-making framework your team has developed for identifying which patients are most likely to benefit from the surveillance approach? How are patients with these tumors risk stratified?

Dr. Tuttle: While the ATA guidelines clearly state that active surveillance “can be considered” for patients with very low-risk thyroid cancer, they provide very little specific guidance in terms of which patient should be selected, which patients should be excluded, and what the follow-up patterns should look like. They do get to examples of what very low-risk thyroid tumors could look like; these include tumors that are thought to be intrathyroidal and without metastasis, as well as the specific example of papillary microcarcinomas, based on the extensive Japanese experience.

In order to help patients and physicians understand the decision-making framework that we employee, we identified 3 domains that need to be carefully evaluated before deciding whether or not the patient should be followed with active surveillance. These included characteristics of the patient, characteristics of the medical team, and the specifics of the biopsy-proven thyroid cancer. Using characteristics for each of these three domains, we classified people as ideal, appropriate, or inappropriate for active surveillance.

The ideal patient is more than 60 years old, with a papillary microcarcinoma confined to the thyroid, presenting as a single nodule well within the thyroid gland with no evidence of lymph node metastasis. Alternatively, inappropriate patients include those in whom the nodule is known to be increasing in size, has demonstrated evidence of extrathyroidal extension, has developed metastatic disease, or is in a location that could result in harm to the patient if even minor disease progression occurred. Appropriate patients, essentially include everybody else, and are usually papillary thyroid carcinoma with less than 1–1.5 cm, confined to the thyroid, if the patient is willing to follow with active surveillance being followed by an experienced multidisciplinary team.

The details of this are given in an article that I wrote with Juan P. Brito and Professors Akira Miyauchi and Yasuhiro Ito, who pioneered active surveillance for papillary microcarcinomas in Japan more than 20 years ago.[1]

Reference

1. Brito JP, Ito Y, Miyauchi, Tuttle RM. A clinical framework to facilitate risk stratification when considering an active surveillance alternative to immediate biopsy and surgery in papillary microcarcinoma. Thyroid. 2016;26:144–149.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.