Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial: Long-Term Follow-Up

The long-term follow-up of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial confirms that finasteride reduces the risk of low-grade prostate cancer by one-third, but there were no significant survival differences between the two study arms.

In 2003, results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) showed that finasteride significantly reduced the risk of a prostate cancer diagnosis, but the study also showed a small increase in the risk of high-grade prostate cancer. These results were after 7 years of patient follow-up. Finasteride has since not been used as a preventive measure because of the concern of potential harm to patients.

Now, the 18-year long-term follow-up of the PCPT study,

But the long-term follow-up also shows that there are no significant differences between the participants who received finasteride or placebo in terms of overall survival rates or survival after a prostate cancer diagnosis.

“The results are reassuring,” wrote Michael LeFevre, MD, of the department of family and community medicine in the School of Medicine at the University of Missouri in Columbia, Missouri. No difference was seen in the overall 15-year survival rate-78% and 78.2% in the finasteride group and the placebo group, respectively. The hazard ratio (unadjusted) for death in the finasteride group was 1.02 (P = .46). However, prostate cancer–specific mortality could not be reported in this follow-up analysis, and the authors noted that small differences in this mortality statistic could exist despite a lack of difference in the overall mortality.

The “safest conclusion,” according to LeFevre, “is that [finasteride] has no short- or long-term effect on all-cause mortality,” which means that it cannot be recommended to prolong patients’ lives. LeFevre also concludes that the effect of finasteride on prostate cancer–specific mortality is likely small, although taking the preventive drug could potentially reduce morbidity as a result of prostate cancer screening and treatment.

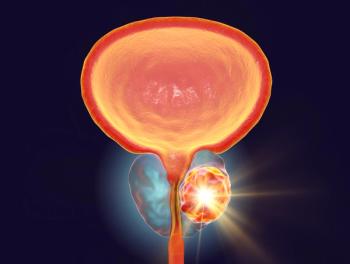

A total of 18,880 men were randomized in the study to receive either finasteride, an inhibitor of the enzyme steroid 5α-reductase that converts testosterone to the androgen dihydrotestosterone, or placebo.

The 10-year survival rates were slightly more varied between the two groups of men with low-grade prostate cancer-83% in the finasteride group and 80.9% in the placebo group-compared with men with high-grade prostate cancer (73% in the active group vs 73.6% in the placebo group). Men with high-grade cancer (Gleason score of 7 to 10) accounted for 3.5% of the finasteride group compared with 3% of the men in the placebo group (P = .05).

Previous analyses of the PCPT study showed that finasteride likely lowers PSA levels, which accounts for the boost in PSA tests and prostate biopsy sensitivity in those on the drug compared with patients not taking finasteride. This increase in sensitivity could explain the skew towards diagnosis of higher-grade prostate cancer in the finasteride group compared with placebo. But the concern that finasteride posed the risk of increasing the rate of high-grade disease prevented the drug from being used for cancer prevention.

Limitations of the current analysis include the use of the Social Security Death Index (SSDI) for data on the survival of trial participants, which did not provide the cause of death for the majority of the men. Additionally, the small number of men with high-grade prostate cancer did not allow for a test of noninferiority between the two groups.

The results of the study underscore the complicated decisions that patients face: to undergo prostate cancer screening or not. Men have a 16.5% chance of being diagnosed with prostate cancer, many with low-grade tumors that are not likely to decrease the patient’s overall survival. PSA screening has increased the rate of overdetection and overtreatment, the reasons why the US Preventive Services Task Force has recommended against PSA screening for healthy men not at high risk for prostate cancer. Still, it’s an individual choice for patients, one that should take into account the potential risks and harms of screening (and treatment).

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.