Articles by Rebecca Bechhold, MD

A recent study examined the influence of social interactions between cancer patients during chemotherapy sessions, finding that patients who spent time with other patients who died within 5 years had an increased risk of dying within 5 years themselves. Pardon me for being underwhelmed.

With some analyses warning of an impending oncologist shortage, are we truly approaching a point of critical need? Are practice extenders such as advanced practitioners the best solution to fill that gap or are there other options?

Continuing to hold institutions to specific outcomes may never result in spending control. We need to educate individual physicians on cost-effectiveness in treatment planning.

You may have missed the report concluding that patients had lower readmission and mortality rates if they were under the care of female hospitalists vs their male counterparts. I know excellent physicians in both camps and some sorry ones as well.

Oncologists deliver news-good and bad-on a daily basis. It is, for me, the most challenging and rewarding part of my job.

Are we failing to be as efficient as we could be in delivering care to cancer patients, particularly in follow-up after treatment?

Likely, most doctors would say they are good listeners. It is an essential skill when studying and practicing medicine. But under stress of limited time or a patient not responding to treatment-maybe our ability suffers a bit. Perhaps we are listening but also talking and not checking for understanding.

Patients continue to say they want more information, so they can make informed decisions. But repeatedly, studies tell us that the patient and the family are not hearing us, not understanding us, or both.

I hope to see many of the exciting agents presented this year become available and affordable for my patients. But when the miracle isn’t happening we have an obligation to talk it out and be candidly compassionate. We need to know when to put the pedal to the metal and when to hit the brake.

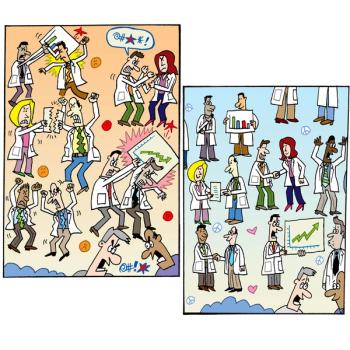

Effective communication between doctors and their team is key to giving the best care to patients, and can provide stress relief in a chaotic day.

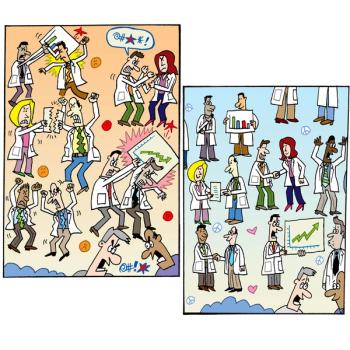

No matter where you practice medicine, if your duties include patient care then you are going to interact with other oncologists. In some cases you may question the quality of their care. Help your peers to become better physicians by respecting them first, then relaying your concerns to them. Here are some examples of how not to do it, paired with kinder, gentler alternatives.

I recently spoke with someone who works for a hospital-based oncology clinic in another state. I am alarmed about the way the practice is structured. There the patient is never treated on the day they see the doctor. That means the patient must make at least two trips for every treatment. But I am told by others that this is standard.

Finding personal interests to discuss with your patient won’t make it all better. but it only takes a moment to find a sliver of common ground, something to make you two humans trying to fix a problem.

No matter how much education my staff and I participate in, we will never cover every single possible adverse event that an individual may experience. And in some cases, when a patient can't explain their symptoms, we can be at a loss as to how to help them.

How do you know your patients are cancer-free? Often hard to answer and often asked with a note of fear suggesting they don't really want to know the answer.

Some of the most brilliant physicians I have known have impressed me with their respect for colleagues. They would never express a difference of opinion by denigrating another practitioner, but recent experiences have opened my eyes to the arrogance of some physicians.

One of the most important questions I ask new patients is what they do for a living, as it opens up a discussion of how important that work is to them.

I do not want politicians passing laws to tell us how to practice. The legislative process cannot keep pace with changes in medicine.

Multiple lines of therapy in stage IV tumors have diminishing benefit, and this is where patients and families need to know that the finish line is the same.

A study was done that showed a video of patients with advanced Alzheimer disease to newly diagnosed dementia patients. Those who watched the videos were far more likely to make decisions against feeding tubes or other aggressive interventions. In this age of GoPro cameras and video capabilities on nearly every phone, are we behind the times?

Oncologists should be experts at farewells. I often write a note of condolence if I have not made personal contact with the patient or family close to the time of death.

When someone states they are “tired,” it prompts follow-up questions regarding activity, sleep, diet, and stress, among other things-just as a complaint of pain leads to where, what kind, and how long.

Each person facing cancer has their own way of coping. They have no obligation to fit a stereotype that others may have conjured up. They are each the poster child of their own unique campaign.

Is there any truth in advertising? A recent study found that cancer center ads only emphasize positive outcomes, but other than direct-to-consumer marketing of pharmaceuticals that list all possible side effects, are you aware of any ads that state less than optimal outcomes?

Oncologists are always queried about how to “eat better so my cancer doesn’t come back.” I have found the most common food issue to be the role of soy in the diet, particularly for hormone-driven breast and prostate cancer patients.

I find it difficult to put a price tag on what I do. It is mainly a thinking profession we are in, though in recent years it has become more like data entry!

Survivorship is very much about lifestyle factors. Diet, exercise, weight control, and alcohol use must be part of our conversation each visit. Patients must see these as part of our “prescription” for their cancer treatment.

If payments were bundled, we would be accountable to evaluate our treatment plans, follow-up visits, tests, and imaging. We need a system that rewards us for excellent care and allows the costs to be presented to our patients.

Why do doctors have such a hard time embracing hospice care and using it to benefit patients, particularly oncology patients? Referring a patient to a hospice program starts a sophisticated plan of care wholly directed at patient comfort, education of the family and grief counseling for the family.